Before the story of my surgical trip to Africa can continue, I need to explain something about what made me a suitable choice to be part of this effort. My story must go backwards a bit before we can move forward.

My Mom wanted me to be self-sufficient in a way that seemed entirely unmanly at the time. I did not come from a moneyed home, and if I tore my jeans, the reality was that I would not get new ones. Sewing was a lesson I learned early on from her, and as a bit of a ruffian who was in a fair number of scuffles that began in my playground days, and remained a theme in my life for many years, I was set on a course that would see a constant flow of more than one or two torn shirts and pants in my wardrobe at any given point in time. Each repair built my skills with needle and thread a bit, aligning edges of jagged tears, finding ways to make them less visible when done, and becoming creative in how a rip with a piece missing, might be put back together so as not to appear lacking in material…… funny how things you learn in one area might be applied to a skill you need in another. Perhaps sewing, when you apply a different name to it, is not such a sissified activity.

There wasn’t much distance between those youthful times, to the day in my last year as a teenager, when I stepped off a plane onto the hot tarmac in Danang, Vietnam. It was a sweltering, muggy day, and within minutes sweat drenched my uniform. It ran down from my neck along my spine. The front of my BDU blouse sprouted dark spots of moisture as every pore opened. It was not yet the sweat that accompanies fear…. that would eventually come, and I didn’t know enough to fear where I was yet. I had been transported from the mild Southern California beaches to a world where the oppressive weather enveloped you, the heaviness of the humid air was palpable in every breath. The weight of it all brought back the same sensation experienced when as a small child, I put on my grandfather’s giant wool overcoat, and almost lost my balance from its weight upon me. Toto, we are definitely not in Kansas anymore…. Torn jeans were going to be the least of my concerns for quite some time. However, there were new tears for repair, and the fabric they were in was something far removed from denim.

Trauma, the kind that occurs in conflict zones around the world, creates wounds unlike what those lucky enough not to be near them, nor one of those sent to engage in them, ever see. Great writers have described those harms in detail and with poignant words, and said it better than I have skill to do. But suffice it to say that it is a kind of physical damage unequaled by many other assaults our body endures. There are injuries that approach it, or equal the intensity of it…. horrible accidents when flying machines succumb to gravity, those perhaps yield something similar. However, as a species we have really worked hard at developing creative ways to maim and kill our fellow man, and torn flesh is the bloody currency of those endeavors. The resulting wounds are often a creative collage of crimson pieces, little resembling the limb or smooth skin that existed only a few moments before. Lesser ones, jagged lacerations from a flying piece of metal, seldom have a linear and precise edge, nor are they free of missing parts. As a corpsman, or “doc” to my marines, I would be the one, at least when in a rear area environment, that would apply my training, both mom’s and the military’s, to closing up what violence had opened. Sewing was now suturing…… and because of repetition and necessity I became good at it. I am confident that the scars I left while permanent, would fade with time. Scars are remembrances. If you own one it marks a particular point in time, accompanied by the memory of its acquisition. Things as simple as learning to ride a bicycle the first time, to medical procedures endured, and then a long list of really dark causes leave them upon us. They will be our lifelong companions. Some will be the subject of bragging rights and war stories told over beers with companions that have their own. Others will be shared by septuagenarians, sitting on a park bench with a crowd of uninterested pigeons at their feet, as they lift up their shirt exposing wrinkled flesh, and complain about the latest medical insult their bodies have had to endure. When my marines rotated back to the “world” (stateside) a fair number of them would own a fibrous scrawl of mine. I wonder what now, so many years later, they remember about a 20-year-old that left that faded mark on them. Perhaps little when compared to the worst of what is now a permanent collection accumulated over many years. My scars will pale in comparison to the really bad ones, ones that will not show on a hot day they spend shirtless at the beach…. those they will carry inside.

For most who do not know me, that preamble about a subject that I seldom discuss was necessary before talking more about Africa. Suturing has not been part of my work life since then, and certainly not part of what I am recognized for in either the implant world nor oral cancer circles. Establishing that I did not jump into what has been transpiring in these Africa posts completely unprepared required a retrospective. Fast forward (finally) many years from using a skill with a regularity that had allowed it to become a respected second nature, to my agreement to travel as Dr. DeLacure’s surgical assistant to a small village in Africa.

While it had not been used for a protracted period of time, I hoped that some of my skill sets would transfer to the operations which I would assist on. I did not know what would be asked of me, and I struggled to remember all the names of instruments I might be called on to employ as Mark asked for them, or directed me to pick up one and use it myself. Army-Navy retractors, rigid rake retractors, Adson retractors. Hell, just the list of retractors was cloudy let alone the clamps, suture types, needle drivers, rat tooth and multiple other forceps types and more. When their sterile wrap was undone and they lay in a stainless pile, a jumble of instruments shining against the sterile cloth on the table, would I even be capable of laying them out in the right order, or remember each by name? Would I be able to mentally keep a count of the 2X2’s we used, numbers of hemostats and more employed? This mental tally is important, (conducted while you are paying serious attention to the surgery that you are engaged in) so that when it came time to close, I would have mentally noted the numbers of each into and out of the operating field to be sure nothing was left behind. Crap, I couldn’t remember where my car keys were this morning… Maybe this was a bad idea. I’m a field trauma tech not a surgical assistant.

Sterile instruments were not my stock in trade. With many years of rust accumulated on previously well-honed skills, I scrambled to become ready. Thank you YouTube for all the “surgical videos for idiots” that you have posted there. Hours into viewing them, instrument names were coming back like old friends who still looked like their high school pictures. At least I was confident of my suturing skills… but with someone of Dr. DeLacure’s skills available, and not working alone as in the past, would my ability even be needed? Doubt filled me, and ran over the edges of my previous confidence in a known skill, blotting out things I previously was sure of. Was I just going to get on that unridden suturing bicycle and ride off flawlessly after it had sat with no air in the tires for so long?

Anyone who knows me understands that if nothing else, I come to a task prepared. I needed to confirm my one strong skill at least, and if necessary, practice in the 6 days that remained before my departure. So my story takes an unexpected detour between here and Africa, on a short trip to an old school meat market in Meridian, Idaho. The family owned market was the kind that still did real butchering; catering to the hunters that brought in the results of a successful venture into Idaho’s backcountry to be turned into steaks, ground meat, and sausages, and local farmers and ranchers who brought in the fruits of their labors. One where cuts of meat unlikely to be found at the local supermarket were laid out on chilled exhibit, waiting for sale in their chrome and glass display cases. When viewed by someone who might normally choose selections at Albertsons, they were resting like little bits of unrecognizable interstellar alien under fluorescent lights. The walls were hung with pictures of hunters, gun in hand posed over their quarry, alongside those of other locals standing next to their blue ribbon steer…. There would be little doubt that shoppers here would be leaving the tidy world of cellophane wrapped meat on neat little Styrofoam trays, and certainly leave with a full understanding of where it all comes from. It was the kind of place where something I needed to practice my skills could surely be found…….

While what I sought was not there in the cases, I was sure it would be in the meat locker in the rear of the store. I pulled a numbered white ticket from the roll designed to keep the customers in order and waited. I was number 13. Great. Good thing that as I prepared to cross the world to a remote location I knew little about, that I am not superstitious by nature. Handing my number to the butcher, I explained my desired purchase, gesturing with my hands as I talked like a fisherman bragging about the size of his catch. “It needs to be about this big…….” Soon he returned from the back with exactly what I needed, a piece of pig skin about 24 by 24 inches’ square and about half an inch thick. Perfect.

Pig tissue is a pretty good analog to our own skin, and the layers of epithelium, fat, and muscle all exist in about the same distribution and thickness as found in the largest organ of the human body. My kitchen table was about to become my operating theater, and soon my “patient” would look more like something that Igor had watched Dr. Frankenstein create in his lab than an innocent piece of pork. Just one more stop at my hangar to retrieve my suturing materials from my airplane’s crash kit; a necessity filled with medical and survival components, and something you never venture into the remote Idaho backcountry without, and I would be ready to refresh those dusty skills.

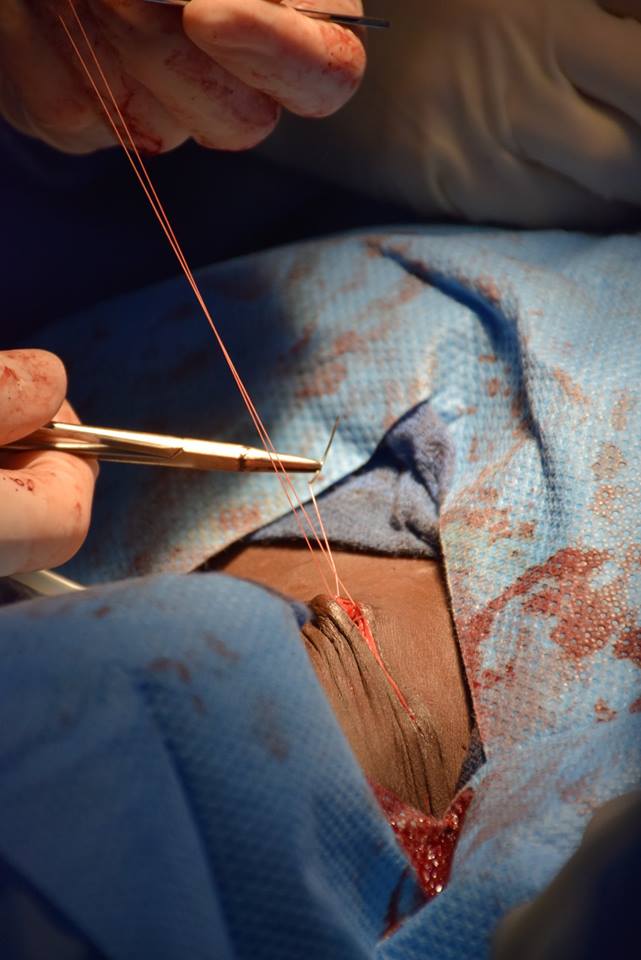

Six days later and I have created incisions in my sample so many times there are few areas unscathed. Each has been carefully sutured closed. Interrupted sutures, subcutaneous sutures, mattress sutures, near near- far far sutures, all practiced repeatedly until my confidence in the skill has been restored. Tomorrow I depart on my trip, and it is time for my pigskin “patient” who has suffered so many wounds and repairs without complaint, to be shipped off to the trash bin for the next pick up. I think I am ready.

Next post – Putting my suturing skills to work.