Sean Marsee

Although oral cancer has taken away the lives of those who have accomplished great things, attention must be paid to those who were taken away before they ever got the chance to reach their goals. High school track star Sean Marsee was one of these.

Sean Marsee was a very popular and respected athlete at his high school in Ada, Oklahoma. A fierce competitor, Sean had won 28 medals at high school track meets in his career. Needless to say, he was in near-perfect physical shape.

He had always taken excellent care of his body, watching his diet, lifting weights, even running five miles a day six months of the year. He didn’t smoke or drink, but Sean was a frequent user of so-called “safe” forms of tobacco, such as chewing tobacco and snuff. Starting at age 12, Sean began to “dip” habitually.

In truth, of course, it wasn’t a habit – it was an addiction. At one point he was going through a can of snuff every day and a half. Sean’s mother, a registered nurse, quickly became aware of the problem. Her lectures on the dangers of tobacco fell on deaf ears, however, as her son simply didn’t believe her warnings of cancer and disease. In his world of track meets and high school, many of his teammates dipped, and even the coach was aware of the habit and didn’t seem to take it seriously. He pointed out to his mother how high profile athletes both used and marketed smokeless tobacco. They were professionals, something Sean himself aspired to be – if they dipped, how could dipping be dangerous?

One day, however, everything changed. Sean came home and told his mother, “Mom, my tongue hurts.” He then showed her a red sore the size of a half-dollar on his tongue, with a hard white core. His mother took him to Dr. Carl Hook, a throat specialist, who recommended a biopsy. Sean was stunned. ” I didn’t know snuff could be that bad for you,” Sean said. Dr. Hook recommended removing that part of Sean’s tongue. Sean was silent for a moment, and then asked, “Can I still run in the state track meet this weekend? And graduate next month?” Dr. Hook agreed, and scheduled the surgery for after Sean’s graduation.

On May 16th, Dr. Hook performed the operation. More of Sean’s tongue had to be removed than was originally planned, and the biopsy results tested positive for cancer. Sean was scheduled to meet with a radiation therapist, but before therapy began, a newly swollen lymph node was found in Sean’s neck. A discouraging sign that the cancer had spread. Sean’s mouth sore had now led to neck surgery.

When it was recommended to the 18-year old that he undergo surgery to remove the lower jaw on the right side along with all lymph nodes, muscles, and blood vessels except his artery, Sean’s mother began to cry. She knew him to be quite careful and concerned with his appearance. “There might be some sinking,” explained the doctor, “but the chin should support the general planes of the face.” After an agonizing ten minutes, Sean finally spoke up. “Not the jawbone. Don’t take the jawbone.” Plans were made to carry out the other parts of the procedure.

On June 20th, Sean underwent his second surgery, lasting eight hours. At his school, teachers and students assembled during their summer vacation to honor their school’s most outstanding athlete. His track coach and his assistant late came to visit Sean and present their gift, a walnut plaque.

After five weeks of healing and radiation therapy, Sean responded well. His mood and body were recovering at a record pace. In October, however, Sean started having severe headaches, and a CAT scan revealed that the cancer had spread anew, around the bottom of his brain and down his back. In November, Sean began his third surgery — the jawbone operation he had not wanted to have and much, much more.

Sean was home that Christmas, maintaining his optimism in the face of such horrible cancer, until January when he found new lumps in the left side of his cheek. The biopsy showed that they too were cancerous.

Even in the midst of this, one day Sean admitted to his mother that he still craved snuff. “I catch myself thinking,” he said, “I’ll just reach over and have a dip.” He also believed that there was a reason for his illness, perhaps in having his story told to others, hopefully “keeping other kids from dying.” Even near the end, when Sean became unable to speak, a friend asked him if there was anything he wanted to tell other young athletes. Sean took a pencil and wrote, “Don’t dip snuff.”

On February 25th, Sean passed away. His track star prowess did not find its zenith, but his bravery and sense of duty to others did.

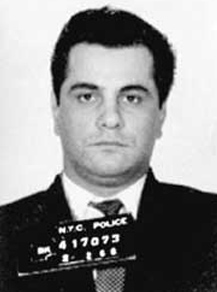

John Joseph Gotti

John Joseph Gotti, one of the most celebrated and feared mobsters in Mafia history, came into the world Oct. 27, 1940, in the Bronx to John and Fannie Gotti. As a youngster, John, fifth of 13 children, moved with his family to Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, then to Brownsville-East, New York.

Gotti seemed to have been born with his fists up. From the fourth grade on, he ran with kid gangs and fought other young toughs, and though he was reportedly a bright student, street lessons occupied more of his attention than those of the classrooms at P.S. 178.

As a young teen, Gotti joined a gang called the Fulton-Rockaway Boys and regularly took on gangs with similar pulp-fictionesque names. Gotti was suspended at 16 and never went back to school.

Gotti tried a brief stint in a garment factory, but soon turned to what for him was an easier and more lucrative living: petty crime. He also began making an impression on influential members of the Mafia’s Gambino family, the largest of the five Mafia groups active then in New York. The Gambino family had its hands in the crime gamut, from theft to gambling to bookmaking, prostitution, and weapons trafficking; Gotti later brought drug trafficking into the mix.

In 1970, the 20-year-old Gotti married Victoria DiGiorgio. The couple moved around for a while, then settled in the Howard Beach-Ozone Park area of Queens. Three years later, the first mob murder tied at least in part to Gotti happened when the mob decided to punish a man named James McBratney, whom it held responsible for the death of Mafia boss Carlo Gambino’s nephew. In May of that year, Gotti and two other men shot and killed McBratney in a Staten Island bar. Gotti plea-bargained and was sentenced to four years, serving only two before being released on parole. He promptly landed back in jail for bookmaking, did a year’s time, then was arrested twice for stealing truckloads of goods and served another three years.

When he got out of prison, Gotti was formally initiated into the Mafia, began running his neighborhood and was soon tucked under the wing of Aniello Dellacroce, a Gambino family underboss. The year was 1980, and Gotti’s family was growing. But one day, Gotti’s favorite son, 12-year-old Frankie, was killed when a middle-aged neighbor, driving home from work and blinded by the afternoon sun, struck the child when he darted into the street on a minibike. The neighbor, Frank Favara, soon began receiving death threats. He ignored them and kept to his usual schedule. Four months later he was kidnapped on his way home from work. His body was never found. The murder was assumed to have been ordered by Gotti, though some thought others had done it in an attempt to impress the increasingly powerful mobster.

Five years later, it was clear that Gotti was poised for a major move within the mob. Other Mafia members were seen showing Gotti extraordinary deference. Early in 1985, Gotti’s original mob mentor had died. Gotti had previously sought to maneuver Dellacroce to the head of the Gambino crime family; Paul Castellano had long since replaced Carlo Gambino as the family’s leader and the move never sat well with Gotti. With Dellacroce dead, it was only natural that Gotti should step forward. On Dec. 16, 1985, Castellano was killed, along with one of his lieutenants, when three gunmen opened fire on them in front of a Manhattan steak house. There was no question about who had ordered the hit. Within days, Gotti (who was never arrested in the Castellano killing) had assumed the Gambino family throne.

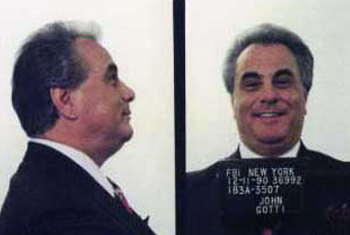

Gotti set up his headquarters at the Ravenite Social Club and began holding court. He quickly gained a reputation for ruthless reprisal to real and rumored offenses. He was unusually flashy for a mobster, wearing expensive and impeccably tailored clothing, eating at the best New York restaurants, and acquiring a celebrity not known in the Mafia world since the days of Al Capone. The press started calling Gotti the Dapper Don. Soon another name, Teflon Don, was added to the list, as the mob bribed and pressured jurors to acquit Gotti in a series of cases against him.

In one, a 1987 racketeering trial, federal agents had what appeared to be a solid case against Gotti. Agents had recorded hours of conversations between the Gambino boss and his cohorts. But mob tactics from Gotti’s thugs and legal strategy from Gotti lawyer Bruce Cutler ensured Gotti’s acquittal. In 1990, a solicitation of murder trial ended the same way, with Gotti even predicting his release before reporters on his way to the courthouse.

But a year later, Gotti was snared in a trap he never saw being set. Gotti’s good friend and close mob associate, Salvatore (Sammy the Bull) Gravano, facing life in prison for murder and racketeering charges, agreed to testify against Gotti in return for a lighter sentence. In 1992, Gravano gave nine days of testimony that fascinated the country, exposing mob tactics to sunlight and spelling the downfall of John Gotti. The jury in this trial was sequestered, and Gotti’s lawyer, Cutler, was prevented from defending him because of conflict of interest. Gotti was found guilty and got life without parole.

Gotti was sent to maximum-security federal penitentiary in Marion, Ill., where he served the next 10 years relatively quietly, resorting to his customary flamboyance whenever interviewers and other visitors came around. Gotti’s son, John Jr., stepped in to assume some of his father’s responsibilities, but was nabbed on racketeering, extortion, and tax evasion charges and was sent to prison (Gotti’s four other offspring chose a life outside the mob).

In 1998, the 57-year-old Gotti was diagnosed with oral cancer and was transferred to a federal prison hospital for treatment. But the cancer spread, and on June 10, 2002, Gotti died of head and neck cancer. The Diocese of Brooklyn would not allow the mobster a Mass of Christian Burial. Gotti was interred in the Gotti family mausoleum at St. John’s Cemetery in New York.