By Edward O. Uthman, MD. Diplomat, American Board of Pathology

Introduction

Many medical conditions, including all cases of cancer, must be diagnosed by removing a sample of tissue from the patient and sending it to a pathologist for examination. This procedure is called a biopsy, a Greek-derived word that may be loosely translated as “view of the living.” Any organ in the body can be biopsied using a variety of techniques, some of which require major surgery (e.g., staging splenectomy for Hodgkin’s disease), while others do not even require local anesthesia (e.g., fine needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid, breast, lung, liver, etc). After the biopsy specimen is obtained by the doctor, it is sent for examination to another doctor, the anatomical pathologist, who prepares a written report with information designed to help the primary doctor manage the patient’s condition properly.

Many medical conditions, including all cases of cancer, must be diagnosed by removing a sample of tissue from the patient and sending it to a pathologist for examination. This procedure is called a biopsy, a Greek-derived word that may be loosely translated as “view of the living.” Any organ in the body can be biopsied using a variety of techniques, some of which require major surgery (e.g., staging splenectomy for Hodgkin’s disease), while others do not even require local anesthesia (e.g., fine needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid, breast, lung, liver, etc). After the biopsy specimen is obtained by the doctor, it is sent for examination to another doctor, the anatomical pathologist, who prepares a written report with information designed to help the primary doctor manage the patient’s condition properly.

The pathologist is a physician specializing in rendering medical diagnoses by examination of tissues and fluids removed from the body. To be a pathologist, a medical graduate (M.D. or D.O.) undertakes a five-year residency training program, after which he or she is eligible to take the examination given by the American Board of Pathology. On successful completion of this exam, the pathologist is “Board-certified.” Almost all American pathologists practicing in JCAHO-accredited hospitals and in reputable commercial labs are either Board-certified or Board-eligible (a term that designates those who have recently completed residency but have not yet passed the exam). There is no qualitative difference between M.D.-pathologists and D.O.- pathologists, as both study in the same residency programs and take the same Board examinations.

Types of biopsy

1. Excisional biopsy

A whole organ or a whole lump is removed (excised). These are less common now, since the development of fine needle aspiration (see below). Some types of tumors (such as lymphoma, a cancer of the lymphocyte blood cells) have to be examined whole to allow an accurate diagnosis, so enlarged lymph nodes are good candidates for excisional biopsies. Some surgeons prefer excisional biopsies of most breast lumps to ensure the greatest diagnostic accuracy. Some organs, such as the spleen, are dangerous to cut into without removing the whole organ, so excisional biopsies are preferred for these.

2. Incisional biopsy

Only a portion of the lump is removed surgically. This type of biopsy is most commonly used for tumors of the soft tissues (muscle, fat, connective tissue) to distinguish benign conditions from malignant soft tissue tumors, called sarcomas.

3. Endoscopic biopsy

This is probably the most commonly performed type of biopsy. It is done through a fiberoptic endoscope the doctor inserts into the gastrointestinal tract (alimentary tract endoscopy), urinary bladder (cystoscopy), abdominal cavity (laparoscopy), joint cavity (arthroscopy), mid-portion of the chest (mediastinoscopy), or trachea and bronchial system (laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy), either through a natural body orifice or a small surgical incision. The endoscopist can directly visualize an abnormal area on the lining of the organ in question and pinch off tiny bits of tissue with forceps attached to a long cable that runs inside the endoscope.

4. Colposcopic biopsy

This is a gynecologic procedure that typically is used to evaluate a patient who has had an abnormal Pap smear. The colposcope is actually a close- focusing telescope that allows the physician to see in detail abnormal areas on the cervix of the uterus, so that a good representation of the abnormal area can be removed and sent to the pathologist.

5. Fine needle aspiration

FNA biopsy. This is an extremely simple technique that has been used in Sweden for decades but has only been developed widely in the US over the last ten years. A needle no wider than that typically used to give routine injections (about 22 gauge) is inserted into a lump (tumor), and a few tens to thousands of cells are drawn up (aspirated) into a syringe. These are smeared on a slide, stained, and examined under a microscope by the pathologist. A diagnosis can often be rendered in a few minutes. Tumors of deep, hard-to-get-to structures (pancreas, lung, and liver, for instance) are especially good candidates for FNA, as the only other way to sample them is with major surgery. Such FNA procedures are typically done by a radiologist under guidance by ultrasound or computed tomography (CT scan) and require no anesthesia, not even local anesthesia. Thyroid lumps are also excellent candidates for FNA.

6. Punch biopsy

This technique is typically used by dermatologists to sample skin rashes and small masses. After a local anesthetic is injected, a biopsy punch, which is basically a small (3 or 4 mm in diameter) version of a cookie cutter, is used to cut out a cylindrical piece of skin. The hole is typically closed with a suture and heals with minimal scarring.

7. Bone marrow biopsy

In cases of abnormal blood counts, such as unexplained anemia, high white cell count, and low platelet count, it is necessary to examine the cells of the bone marrow. In adults, the sample is usually taken from the pelvic bone, typically from the posterior superior iliac spine. This is the prominence of bone on either side of the pelvis underlying the “bikini dimples” on the lower back/upper buttocks. Hematologists do bone marrow biopsies all the time, but most internists and pathologists and many family practitioners are also trained to perform this procedure.

With the patient lying on his/her stomach, the skin over the biopsy site is deadened with a local anesthetic. The needle is then inserted deeper to deaden the surface membrane covering the bone (the periosteum). A larger rigid needle with a very sharp point is then introduced into the marrow space. A syringe is attached to the needle and suction is applied. The marrow cells are then drawn into the syringe. This suction step is occasionally uncomfortable, since it is impossible to deaden the inside of the bone. The contents of the syringe, which to the naked eye looks like blood with tiny chunks of fat floating around in it, is dropped onto a glass slide and smeared out. After staining, the cells are visible to the examining pathologist or hematologist.

This part of procedure, the aspiration, is usually followed by the core biopsy, in which a slightly larger needle is used to extract core of bone. The calcium is removed from the bone to make it soft, the tissue is processed (see “Specimen Processing,” below) and tissue sections are made. Even though the core biopsy procedure involves a bigger needle, it is usually less painful than the aspiration.

Specimen processing

After the specimen is removed from the patient, it is processed in one or both of two major ways:

1. Histologic sections. This involves preparation of stained, thin (less than 5 micrometers, or 0.005 millimeters) slices mounted on a glass slide, under a very thin pane of glass called a cover slip. There are two major techniques for preparation of histologic sections:

2. Permanent sections. This technique gives the best quality of specimen for examination, at the expense of time. The fresh specimen is immersed in a fluid called a fixative for several hours (the necessary time dependent on the size of the specimen). The fixative, typically formalin (a 10% solution of formaldehyde gas in buffered water), causes the proteins in the cells to denature and become hard and “fixed.” Adequate fixation is probably the most important technical aspect of biopsy processing.

The fixed specimen is then placed in a machine that automatically goes through an elaborate overnight cycle that removes all the water from the specimen and replaces it with paraffin wax. The next morning, a technical professional, called a histologic technician, or “histotech,” removes the paraffin-impregnated specimen and “embeds” it in a larger bloc of molten paraffin. This is allowed to solidify by chilling and is set in a cutting machine, called a microtome. The histotech uses the microtome to cut thin sections of the paraffin block containing the biopsy specimen. These delicate sections are floated out on a water bath and picked up on a glass slide.

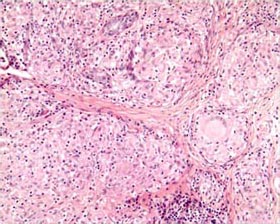

The paraffin is dissolved from the tissue on the slide. With a series of solvents, water is restored to the sections, and they are stained in a mixture of dyes. The most common dyes used are hematoxylin a natural product of the heartwood of the logwood tree, Haematoxylon campechianum, which is native to Central America, and eosin, an artificial aniline dye. The stain combination, casually referred to by pathologists as “H and E” yields pink, orange, and blue sections that make it easier for us to distinguish different parts of cells. Typically, the nucleus of cells stains dark blue, while the cytoplasm stains pink or orange.

3. Frozen sections. This technique allows one to examine histologic sections within a few minutes of removing the specimen from the patient, but the price paid is that the quality of the sections is not nearly as good as those of the permanent section. Still, a skilled pathologist and a knowledgeable surgeon can work together to use the frozen section’s rapid availability to the patient’s great benefit.

4. Smears. The specimen is a liquid, or small solid chunks suspended in liquid. This material is smeared on a microscope slide and is either allowed to dry in air or is “fixed” by spraying or immersion in a liquid. The fixed smears are then stained, coverslipped, and examined under the microscope.

Like the frozen section, smear preparations can be examined within a few minutes of the time the biopsy was obtained. This is especially useful in FNA procedures (see above), in which a radiologist is using ultrasound or CT scan to find the area to be biopsied. He or she can make one “pass” with the needle and immediately give the specimen to the pathologist, who can within a few minutes determine if a diagnostic specimen was obtained. The procedure can be terminated at that point, sparing the patient the discomfort and inconvenience of repeated sticks.

Pathologic examination

The gross description

The pathologist begins the examination of the specimen by dictating a description of the specimen as it looks to the naked eye. This is the “gross exam” or the “gross.” Some pathologists may refer to the gross exam as the “macroscopic.” Most biopsies are small, nondescript bits of tissue, so the gross description is brief and serves mostly as a way to code which biopsy came from what area and to use for troubleshooting if there is a question of specimen mislabeling. A typical gross description of an endoscopic colon biopsy follows:

“Polyp of sigmoid colon.” An ovoid, smooth- surfaced, firm, pale tan nodule, measuring 0.6 x 0.4 x 0.3 cm. Cassette ‘A’, all, bisected. In the above example, the first item (in quotes) is an exact recitation of how the specimen was labeled by the doctor who took the biopsy. After that is a textual description of what the specimen looked like, followed by measurements indicating its size. The “Cassette ‘A’, all, bisected” phrase indicates that the specimen was cut in half (“bisected”), submitted for tissue processing in its entirety (“all”) in a small container (cassette) labeled “A,” which will eventually be placed in the tissue processor.

Larger organs removed as biopsies have correspondingly longer and more detailed gross descriptions. The following is the gross description of a spleen removed to assess whether Hodgkin’s disease (a cancer of lymph tissues) has spread into it:

“Spleen”. An entire spleen, weighing 127 grams, and measuring 13.0 x 4.1 x 9.2 cm. The external surface is smooth, leathery, homogeneous, and dark purplish-brown. There are no defects in the capsule. The blood vessels of the hilum of the spleen are patent, with no thrombi or other abnormalities. The hilar soft tissues contain a single, ovoid, 1.2-cm lymph node with a dark grey cut surface and no focal lesions.

On section of the spleen at 2 to 3 mm intervals, there are three well-defined pale-grey nodules on the cut surface, ranging from 0.5 to 1.1 cm in greatest dimension. The remainder of the cut surface is homogeneous, dark purple, and firm.

Summary of cassettes: 1, hilar blood vessels; 2, hilar lymph node, entirely submitted; 3 – 6 spleen nodules, entirely submitted; 7 – 8, spleen, away from nodules.

In the spleen described above, the pathologist found a few lumps (nodules), representing the most important data in this gross examination. These possibly represent the tumors of Hodgkin’s disease, subject to confirmation by the microscopic examination. Much of the remainder of the verbiage relates to “pertinent negatives,” or things that were routinely looked for but not found, such as a rupture of the spleen capsule (suggesting an intraoperative accident), blood clots (“thrombi”) in the vessels supplying the spleen, and evidence of an infection (in which case the cut surface of the spleen would be soft instead of firm). In addition, a lymph node was serendipitously found adherent to the spleen, and this was briefly described as having a normal appearance.

The last paragraph of the gross description gives the identifying “codes” of the slices of the specimen submitted for microscopic examination in cassettes. The microscope slides prepared from the processed samples will be labeled with the same numbers as the cassettes, and the pathologist doing the microscopic examination can, by referring to the typed gross description, know from what part of the specimen the tissue on the slide came.

The microscopic examination

The microscopic description, or the “micro” is a narrative description of the findings gained from examination of the glass slides under the microscope. The micro is considered somewhat “optional” in a written report. In such a case, the diagnosis (see below) is considered to speak for itself. Here is a the microscopic description on the report of the colon biopsy given above:

Specimen A: The sections show a polypoid structure consisting of a central fibrovascular core, surrounded by a mantle of mucosa showing an adenomatous architecture with a predominantly tubular pattern. The tubules are lined by tall columnar epithelium showing nuclear pseudostratification, hyperchromasia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of cytoplasmic mucin. There is no evidence of stromal invasion. It can be readily seen that the language of microscopy is much more arcane than that used for gross descriptions. It is way beyond the scope of this monograph to cover the nuances of descriptive microscopic pathology. In general, microscopic descriptions are communications between pathologists for referral and quality assurances purposes.

The diagnosis

This is analogous to the “bottom line” of a financial report. The purpose of the gross examination, the processing of the tissue, and the microscopic examination is to build a logical argument toward a terse assessment of what significance the biopsy has in regard to the patient’s health. Here is the diagnosis for the colon biopsy, above:

Colon, sigmoid, endoscopic biopsy: tubular adenoma (adenomatous polyp) This format is widely used, but variations occur. The first term is the organ or tissue involved (“colon”). The second term (“sigmoid”) specifies the site in the colon from which the biopsy was obtained. The next term (“endoscopic biopsy”) denotes the type of surgical procedure used in obtaining the biopsy. Then follows the diagnosis proper, in this case “tubular adenoma,” a common benign tumor of the large intestine and rectum, which increases the risk for developing colorectal cancer in the future. In this particular case, an older synonym for tubular adenoma, “adenomatous polyp,” follows in parentheses.

Glossary of important terms

Finally, it may be useful to present a brief glossary of important terms used in pathologic diagnoses. Terms in the definition that are in ALL CAPS have their own entry.

ABSCESS

A closed pocket containing pus. Some abscesses are easily diagnosed clinically, as they are painful and may “point out” such that pus becomes visible, but deep and chronic abscesses may just look like a TUMOR clinically and require biopsy to distinguish them from neoplasm.

ATYPICAL

The simple, straightforward definition would be “unusual,” but “atypical” means much more than that. In a diagnosis, the use of the term atypical is a vague warning to the physician that the pathologist is worried about something, but not worried enough to say that the patient has cancer. For instance, lymphomas (cancers of the lymph nodes) are notoriously difficult to diagnose. Some lymph node biopsies are very disturbing but do not quite fulfill the criteria for cancer. Such a case may be diagnosed as “atypical lymphoid HYPERPLASIA.” Other important atypical hyperplasias are those of the breast (atypical ductal hyperplasia and atypical lobular hyperplasia) and the lining of the uterus (atypical endometrial hyperplasia). Both of these conditions are thought to be precursor warning signs that the patient is at high risk of developing cancer of the respective organ (breast and uterus).

CARCINOMA

A malignant NEOPLASM whose cells appear to be derived from EPITHELIUM. This word can be used by itself or as a suffix. Cancers composed of columnar epithelial cells are often called adenocarcinomas. Those of squamous cells are called squamous cell carcinomas. The type of cancer typically recapitulates the type of epithelium that normally lines the affected organ. For instance, almost all cancers of the colon are adenocarcinomas, and columnar epithelium is the normal lining of the colon. There are exceptions, however.

DYSPLASIA

An ATYPICAL proliferation of cells. This may be loosely thought of as an intermediate category between HYPERPLASIA and NEOPLASIA. It finds its best use as a term to describe the phenomenon in which EPITHELIUM proliferates and develops the microscopic appearance of neoplastic tissue, but otherwise tends to “behave itself” and continues to line body surfaces without actually invading them, as a true malignant neoplasm would do. It may be convenient (but not totally accurate) to consider dysplasia as a “pre-cancer” or an incipient cancer. Probably the most commonly occurring type of dysplasia is that of the cervix of the uterus, where a progression from dysplasia to neoplasia can be clearly demonstrated. Other dysplasias, such as those of the breast and prostate, are more difficult to clearly relate to neoplasia at this time.

EPITHELIUM

A specialized type of tissue that normally lines the surfaces and cavities of the body. There are three main types: 1) columnar epithelium, which lines the stomach, intestines, trachea and bronchi, salivary and other glands, pancreas, gallbladder, nasal cavity and sinuses, uterus (including inner cervix), Fallopian tubes, kidneys, testes, vasa deferentia, and other ductal structures, 2) stratified squamous epithelium, which lines the skin, oral cavity, throat, esophagus, anus, outer urethra, vagina, and outer cervix, and 3) transitional epithelium (urothelium), which lines the urine-collecting part of the kidneys, the ureters, bladder, and inside part of the urethra.

GRANULOMA

A special type of INFLAMMATION characterized by accumulations of macrophages, some of which coalesce into “giant cells.” Granulomatous inflammation is especially characteristic of tuberculosis, some deep fungal infections (like histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis), sarcoidosis (a disease of unknown cause), and reaction to foreign bodies.

HYPERPLASIA

A proliferation of cells which is not NEOPLASTIC. In some cases, this may be a result of the body’s normal reaction to an imbalance or other stimulus, while in other cases the physiologic cause of the proliferation is not apparent. An example of the former process is the enlargement of lymph nodes in the neck as a result of reaction to a bacterial throat infection. The lymphocytes which make up the node divide and proliferate, taking up more volume in the node and causing it to expand. An example of hyperplasia in which the stimulus is not known is benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), in which the prostate gland enlarges in older men for no known reason. While hyperplasia’s do not invade other organs or METASTASIZE to other parts of the body, they can still cause problems because of their local physical expansion. For instance, in BPH, the enlarged prostate pinches off the urethra and interferes with the flow of urine. If untreated, permanent kidney damage can result.

INFLAMMATION

A reaction, usually mediated by the immune system, to noxious stimuli, manifested clinically by swelling, pain, tenderness, redness, heat, and/or loss of function of the affected part. To a pathologist, however, inflammation means the infiltration of certain immune system cells into the tissue or organ being examined. These inflammatory cells include 1) neutrophils, which are the white blood cells that make up pus and are seen in acute or early inflammations, 2) lymphocytes, which are typically seen in more chronic or longstanding inflammations, and 3) macrophages (histiocytes), which are also seen in chronic inflammation. Some types of inflammation are readily diagnosable by the primary care physician, such as an infected skin wound that is tender, hot, and draining pus. Other types of inflammation are not so readily apparent clinically and require biopsy to distinguish them from neoplasms. The suffix “-itis” is appended to a root word to indicate “inflammation of _____.” For example, cervicitis, pharyngitis, gastritis, and thyroiditis are inflammations of the cervix, pharynx (throat), stomach, and thyroid gland, respectively.

LESION

This is a vague term meaning “the thing that is wrong with the patient.” A lesion may be a TUMOR, an area of INFLAMMATION, or an invisible biochemical abnormality (like the abnormality of the sensitivity of the body’s cells to insulin in adult-onset diabetes). METAPLASIA.

The phenomenon by which one type of tissue is replaced by another type. This often results from chronic irritation of an EPITHELIAL lining. A good example is the cervix, in which chronic irritation and INFLAMMATION causes the relatively delicate normal columnar epithelium to be replaced by tougher squamous epithelium (similar to that which normally lines the vagina, which is naturally “built tougher” for obvious reasons). This phenomenon is called “squamous metaplasia.” In it’s pure state, metaplasia is not harmful, but some metaplasias are markers for increased risk of more serious diseases. For instance, a type of intestinal metaplasia of the stomach (in which columnar epithelium of the intestinal type replaces that of the gastric type) is considered a risk factor for the subsequent development of cancer of the stomach.

METASTATIC

Of or pertaining to METASTASIS, or the process by which malignant NEOPLASMS can shed individual cells, which can travel through the lymph vessels or blood vessels, lodge in some distant organ, and grow into tumors in their own right. There are two major routes of metastasis, 1) hematogenous, in which the cells travel through the blood vessels, and 2) lymphogenous, in which the lymphatic vessels conduct the cancer cells. In the case of lymphogenous metastasis, the metastatic tumors can grow from cancers cells entrapped in the lymph nodes that collect the lymph draining from the organ where the original cancer has developed, causing the nodes to enlarge. In the case of breast cancer, the axillary (underarm) nodes are the first to become involved. In the case of cancer of the larynx (voice box), the nodes on either side of the neck (cervical nodes) are first. Hematogenous metastases tend to deposit in the lungs, liver, and brain. Many cancers metastasize both lymphogenously and hematogenously. Most cancer operations attempt to remove not only the cancerous organ, but also the lymph nodes that drain that organ. Some types of cancer, especially the most common ones (lung, breast, colon, and prostate cancers) tend to metastasize to lymph nodes first. Pathologic examination of these nodes is important in “staging” the cancer, which gives the patient and the doctor some idea as to the odds of curing the cancer and how to best treat it. A typical diagnosis of a specimen of a “radical” removal of a cancer may read like:

Breast, left, mastectomy: infiltrating ductal carcinoma; three of fifteen axillary nodes contain metastatic carcinoma.

NECROSIS

Death of tissue. Necrosis may be seen in inflammatory conditions, as well as in NEOPLASMS.

NEOPLASM, or NEOPLASIA

A “new growth” of the body’s own cells, a proliferation of cells no longer under normal physiologic control. These may be “benign” or “malignant.” Benign neoplasms are typically tumors (lumps or masses) that, if removed, never bother the patient again. Even if they are not removed, they are not capable of destroying adjacent organs or “seeding” out to other parts of the body. Malignant neoplasms, or “cancers,” are those whose natural history (i.e., behavior if untreated) is to cause the death of the patient. Malignancy is expressed by 1) local invasion, in which the neoplasm extends into vital organs and interferes with their function, 2) METASTASIS, in which cells from the tumor seed out to other parts of the body and then grow into tumors themselves, and/or 3) paraneoplastic syndromes, in which the neoplasm secretes metabolic poisons or inappropriately large amounts of hormones that cause problems with functions of various body systems.

-OMA

This suffix means “tumor” or “lump.” It typically, but not invariably, refers to a NEOPLASM (“GRANULOMA” is an exception). In referring to neoplasms, benign ones are typically referred to by a word, the prefix of which refers to the organ or tissue of origin, followed by the suffix “-oma.” For example, leiomyoma, osteoma, chondroma, adenoma, and hemangioma, refer to benign neoplasms of smooth muscle, bone, cartilage, glandular tissue, and blood vessel tissue, respectively. The analogous terms for malignant versions of these neoplasms are, leiomyosarcOMA, osteosarcOMA, chondrosarcOMA, adenocarcinOMA, and angiosarcOMA. There are exceptions to these vocabulary rules. For instance, hepatomas and melanomas are all malignant. Other tumors, such as those of the adrenal glands, cannot be classified into benign or malignant categories based on pathologic appearance. Only their behavior in time shows their true colors. An example is pheochromocytoma (a tumor of the adrenal medulla), ten per cent of which are malignant, but we don’t know just by looking at the tumor if a given case will fall into that ten per cent.

POLYP

A structure consisting of a rounded head attached to a surface by a stalk (also called a “pedicle” or “peduncle”). A mushroom growing from the soil is an excellent example of what a polyp looks like. Polyps may be HYPERPLASTIC, METAPLASTIC, NEOPLASTIC, INFLAMMATORY, or none of the above. The typical polyps removed from the colon of adults during colonoscopy are benign neoplasms called tubular adenomas or adenomatous polyps. The typical nasal polyps that develop in people with allergies are inflammatory. The common benign polyps removed from the cervix are of uncertain origin.

SARCOMA

A malignant NEOPLASM whose cells appear to be derived from those other than EPITHELIUM. The connective tissues of the body (fibrous tissue, muscle, bone, cartilage, fat, and lining of joints) tend to give rise to sarcomas. In adults, CARCINOMAS are much more common than sarcomas. This makes sense, because as we age, our body linings are assaulted by one noxious substance after the other. So it is no surprise that those epithelial cells on the forefront of our battle with the environment are the first to lose control of their growth and development. In children, sarcomas make up a greater proportion of cancers. While the connective tissues of adults are rather stable and protected from environmental assault, those of children are still growing and developing, the cells dividing, raising the likelihood that something will go haywire and cause a cell to lose control over its growth.

SUPPURATION, SUPPURATIVE INFLAMMATION

A type of acute INFLAMMATION characterized by infiltration of neutrophils at the microscopic level and formation of pus at the gross level. ABSCESS is special type of suppurative inflammation. TUMOR.

A mass or lump that can be felt with the hand or seen with the naked eye. This may be a NEOPLASM, HYPERPLASIA, distention, swelling, or anything that causes a local increase in volume. The thing to remember is that not all tumors are cancers, and not all cancers are tumors.

This article is provided as is without any expressed or implied warranties. While every effort has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information, the author assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from use of the information herein.

Copyright (c) Edward O. Uthman. Version 1.002