Background:

Pigmented entities are relatively common in the oral mucosa and arise from intrinsic and extrinsic sources. Conditions such as melanotic macules, smoker’s melanosis, amalgam and graphite tattoos, racial pigmentation, and vascular blood-related pigments occur with some frequency. Addison disease and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome also appear in perioral and oral locations as pigmented macules. Oral pigmentations may range from light brown to blue-black, red, or purple. The color depends on the source of the pigment and the depth of the pigment from which the color is derived. Melanin is brown, yet it imparts a blue, green, or brown color to the eye. This effect is due to the physical properties of light absorption and reflection described by the Tyndall light phenomenon or effect. Oral conditions with increased melanin pigmentation are common; however, melanocytic hyperplasias are rare. Clinicians must visually inspect the oral cavity, obtain good clinical histories, and be willing to perform a biopsy in any condition that is not readily diagnosed. Patients with oral malignant melanoma often recall having an existing oral pigmentation months to years before diagnosis, and the condition may even have elicited prior comment from physicians or dentists.

Pathophysiology:

Oral melanomas are uncommon, and, similar to their cutaneous counterparts, they are thought to arise primarily from melanocytes in the basal layer of the squamous mucosa. Melanocytic density has a regional variation. Facial skin has the greatest number of melanocytes. In the oral mucosa, melanocytes are observed in a ratio of about 1 melanocyte to 10 basal cells.

In contrast to cutaneous melanomas, which are etiologically linked to sun exposure, risk factors for mucosal melanomas are unknown. These melanomas have no apparent relationship to chemical, thermal, or physical events (eg, smoking; alcohol intake; poor oral hygiene; irritation from teeth, dentures, or other oral appliances) to which the oral mucosa constantly is exposed. Although benign, intraoral melanocytic proliferations (nevi) occur and are potential sources of some oral melanomas; the sequence of events is poorly understood in the oral cavity. Currently, most oral melanomas are thought to arise de novo.

Although rare, tumor transformation of nevi to melanoma involves the clonal expansion of cells that acquire a selective growth advantage. This transformation of melanocytes in an existing nevus, or of single melanocytes in the basal cell layer, must occur before the altered cells proliferate in any dimension.

In cutaneous melanomas, well-known differences exist in the biologic behaviors of the radial growth phase–melanoma (flat or macular), vertical growth phase–melanoma (mass, nodule, elevation), and vertical growth phase–melanoma with metastasis.

Some authorities (Elder et al) have stated that these different growth patterns require cellular alteration or transformation to progress to the next, more biologically aggressive phase. Radial growth phase–melanomas do not tend to invade the underlying reticular dermis, but they are associated with metastasis. Vertical growth phase–melanomas, though invasive, must achieve some competence before subsequent metastasis can occur.

Elder et al have described this progression and state that differences in each phase are qualitative. However, phase progression is not absolute because most benign melanocytic lesions do not evolve into melanoma. Melanoma development requires a biochemical alteration in the precursor cells undergoing clonal expansion. This alteration triggers accelerated growth and invasive potential, but not necessarily progression from horizontal to vertical growth phases.

The oral mucosa has an underlying lamina propria, not a papillary and reticular dermis with easily discernible boundaries as observed in skin. This architectural difference obviates the use of Clark levels for describing oral mucosal melanomas.

Rates of occurrence:

-

U.S. Surveillance data are not available for oral melanoma alone. Data for oral melanoma are included in the combined statistics for oral cancer. In a review of the large studies, melanoma of the oral cavity is reported to account for 0.2-8% of melanomas and approximately 1.6% of all malignancies of the head and neck. In some studies, primary lesions of the lip and nasal cavity also are included in the statistics, thereby increasing the incidence.

-

The oral mucosa is primarily involved in fewer than 1% of melanomas, and the most common locations are the palate and maxillary gingiva. Metastatic melanoma most frequently affects the mandible, tongue, and buccal mucosa.

In contrast to the incidence of cutaneous melanoma, the incidence of oral melanoma has remained stable for more than 25 years.

- Internationally, oral melanoma is more common in the Japanese than in other groups. In Japan, oral melanomas account for 11-12.4% of all melanomas, and males may be affected slightly more often than females. This percentage is higher than the 0.2-8% reported in the United States and Europe. Because cutaneous melanoma is less common in more darkly pigmented races, people of these races have a greater relative incidence of oral mucosal melanoma.

The prevalence of oral melanoma in the Japanese population is somewhat controversial. Authorities state that, as with cutaneous melanoma, oral mucosal melanomas are more common in whites than in other groups.

Mortality/Morbidity:

Oral melanoma often is overlooked or clinically misinterpreted as a benign pigmented process until it is well advanced. Radial and vertical extension is common at the time of diagnosis. The anatomic complexity and lymphatic drainage of the region dictate the need for aggressive surgical procedures.

- The prognosis is poor, with a 5-year survival rate generally in the range of 10-25%. The median survival is less than 2 years. As a result of the absence of corresponding histologic landmarks in the oral mucosa (ie, papillary and reticular dermis), Clark levels of cutaneous melanoma are not applicable to those of the oral cavity. Conversely, tumor thickness or volume may be a reliable prognostic indicator.

- The relative rarity of mucosal melanomas has dictated that tumor staging be based on the broader experience with cutaneous melanoma. Oral melanomas seem uniformly more aggressive and spread and metastasize more rapidly than other oral cancers or cutaneous melanomas. Early recognition and treatment greatly improves the prognosis.

- In one large study (1074 mucosal melanomas), when lymph node status was known, 30% of patients with mucosal melanomas had positive nodes. When lymph node metastasis occurs, the prognosis worsens precipitously. For instance, the 5-year survival rate in patients with positive nodes is 16.4% as opposed to 38.7% in patients with negative nodes.

Race:

- Oral melanoma reportedly occurs more commonly in the Japanese than in other groups. This observation is based on a review of frequently cited historical literature. As some authorities have stated, oral malignant melanoma, although rare in whites, is still more common in whites than in the pigmented races.

- A separate categorization of “oral mucosal melanoma” in the cancer surveillance data reported in the United States and by the World Health Organization could be used to clarify race and sex prevalence. Until it is, statistics will continue to be derived from case reports and review articles that reflect the opinion of those authors.

Sex:

- A male predilection exists, with a male-to-female ratio of almost 2:1. Oral melanoma is diagnosed approximately a decade earlier in males than in females.

- This ratio is contrasted with the roughly equal sex distribution of cutaneous melanoma. In Japan, data suggest an equal or slight male predilection.

Age:

- Oral malignant melanoma is largely a disease of those older than 40 years, and it is rare in patients younger than 20 years.

- The average patient age at diagnosis is 56 years. Oral malignant melanoma is commonly diagnosed in men aged 51-60 years, whereas it is commonly diagnosed in females aged 61-70 years.

CLINICAL

History:

- Oral melanomas arise silently, with few symptoms until progression has occurred.

- Most people do not inspect their oral cavity closely, and melanomas are allowed to progress until significant swelling, tooth mobility, or bleeding causes them to seek care.

- Pigmented lesions 1.0 mm to 1.0 cm or larger are found.

- Reports of previously existing pigmented lesions are common. These lesions may represent unrecognized melanomas in the radial growth phase.

- Amelanotic melanoma accounts for 5-35% of oral melanomas.

- This melanoma appears in the oral cavity as a white, mucosa-colored, or red mass.

- The lack of pigmentation contributes to clinical and histologic misdiagnosis.

Physical:

- Because oral malignant melanomas are often clinically silent, they can be confused with a number of asymptomatic, benign, pigmented lesions.

- Oral melanomas are largely macular, but nodular and even pedunculated lesions occur.

- Pain, ulceration, and bleeding are rare in oral melanoma until late in the disease.

- The pigmentation varies from dark brown to blue-black; however, mucosa-colored and white lesions are occasionally noted, and erythema is observed when the lesions are inflamed.

- The palate and maxillary gingiva are involved in approximately 80% of patients, but buccal mucosa, mandibular gingiva, and tongue lesions are also identified.

- The oral mucosa is primarily involved in fewer than 1% of melanomas.

- Metastatic melanoma most frequently affects the mandible, tongue, and buccal mucosa.

- Features of long-standing lesions include elevation, color variegation, ulceration, and satellite lesions that may have the appearance of physiologic pigmentation.

- A neck mass may be present, indicating regional metastasis; however, this is rare unless the primary tumor is extensive.

Causes:

- The cause of oral melanoma or melanoma of any mucosal surface remains unknown, and the incidence has remained stable for more than 25 years. In contrast, cutaneous lesions are linked directly to fair-skinned and blue-eyed persons with a history of blistering sunburns, and incidence has increased dramatically over the same time period.

- The predilection for occurrence in the palate remains a mystery.

- No link has been established with denture wearing, chemical or physical trauma, or tobacco use.

- Melanocytic lesions, such as blue nevi, are more common on the palate.

- Oral blue nevi are not reported to undergo malignant transformation.

Differentials to be considered

Addison Disease

Blue Nevi

Ephelides (Freckles)

Kaposi Sarcoma

Oral Nevi

Other Problems to be Considered:

- Amalgam tattoo

- Graphite tattoo

- Oral melanotic macule

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

- Physiologic pigmentation

The amalgam tattoo is a frequent finding in persons who have had amalgam restorations (ie, fillings). When the amalgam is removed with a high-speed dental handpiece, amalgam particles can be embedded or traumatically implanted in the oral mucosa. Silver from the amalgam leeches out of the embedded particles and stains (ie, tattoos) selected components of the fibrous connective tissue (eg, elastic, reticulin, oxytalan fibers) and highlights the blood vessels. The pigment is often solitary, macular, gray-black, and found near where amalgams were placed and subsequently removed. The gingiva, palate, lateral tongue, and buccal mucosa are commonly involved sites. If the particle is large enough, a dental radiograph may show radiopaque amalgam particles in the soft tissue or bone. Fragments of the amalgam can be observed on histologic specimens, and, on occasion, a foreign body giant cell reaction is noted.

Graphite tattoos result from pencil lead that is traumatically implanted, usually during the elementary school years. A gray-black pigmented, often macular area, commonly found in the palate, corresponds to the size of the implanted lead or the rub from its introduction. Older persons with these tattoos may not be able to recall the event.

Lead shot and bullets also leave rub tattoos in the soft tissue of people who experience such violence.

Although asphalt tattoos are less common on mucosal surfaces than on cutaneous surfaces, they are a source of pigmentation. These tattoos can occur after people slide across paved surfaces.

Intentional tattoos are readily identifiable. They are often vulgarities, letters, or symbols placed by the person or a tattoo artist, and they are often deeply pigmented with a variety of colors. In some cases of self-mutilating behavior, the tattoos are blotchy, irregular, and alarming in appearance.

Coloration imparted by blood can result from the pooling of RBCs in vessels (eg, hyperemia, sludging, presence of a thrombus), increased vascularity, or extravasation after an injury. The red, blue, or purple color due to intravascular blood can be blanched during diascopy, in which pressure is placed on the mucosa by using a glass slide or a test tube. This examination can be used to identify telangiectasias, varicosities, and hemangiomas, to an extent. Kaposi sarcoma, which is often observed in the mouths of patients with AIDS, is a red-to-violaceous, vascular proliferation caused by human herpesvirus 8; it does not blanch on diascopy. The discoloration is due to extravasation of blood coupled with vascular proliferation.

Ecchymosis and petechiae, due to bruising and negative pressure, are common in the junctional area of the hard and soft palates. These conditions do not blanch with pressure because of blood extravasation. The coloration can vary from blue to red to brown. The greens and yellows associated with hemolysis on the cutaneous surfaces are not commonly observed intraorally.

Melanin pigmentation is a common feature of the oral mucosa. This pigmentation is observed diffusely as racial pigmentation, which can be patchy, and focally as melanotic macules and nevi. The relative constancy of the brown color, without variegation, indicates its benign status. However, melanoacanthoma, which is deeply brown-black, can arise suddenly and grow large. Although melanoacanthoma commonly occurs on the buccal mucosa of black women, it can appear on the palate. The lesion is often suggestive of melanoma; however, it represents a benign, possibly reactive process.

Melanotic macules are common on the lip, but they are also found in the oral cavity. They can be extensive in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and are perioral or intraoral. In addisonian pigmentation and pigmentation caused by certain medications, the etiology involves the activity of melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH). Bronzing associated with adrenal insufficiency is diffuse and commonly uniform. When the adrenal cortex does not respond to pituitary-released adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), the continued release depletes ACTH. A precursor protein to ACTH and MSH is released (pro-opiomelanocortin); this protein causes the increased pigmentation.

Medication-induced pigment may be more localized and blotchy. AZT is often a culprit.

Workup

Lab Studies:

- The only study effective in diagnosing oral malignant melanoma is tissue biopsy.

- Perform clinical examination and biopsy of suspicious unexplained lesions.

Imaging Studies:

- Imaging studies, such as computed tomography (CT), may be of benefit in determining the extent of the tumor when contrast enhancement is used.

- Contrast-enhanced CT can be used to determine the extent of the melanoma and whether local, regional, or lymph node metastasis is present.

- Studies such as bone scanning with a gadolinium-based agent and chest radiography can be beneficial in assessing metastasis.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to diagnose melanoma in soft tissue.

- Atypical intensity is correlated with the amount of intracytoplasmic melanin.

- On T1-weighted images, such melanomas are hypointense

- On T2-weighted images, such melanomas are hyperintense and show increased melanin production.

- To the author’s knowledge, oral melanomas are not assessed in this manner.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) has poor results in distinguishing melanoma from nevi. However, combined PET-CT may have diagnostic value.

- Surgical lymph node harvesting depends on the identification of positive nodes at clinical or imaging examination.

Procedures:

- The palate and oral cavity are readily accessible for visual inspection.

- Perform clinical examination and biopsy of suspicious unexplained lesions.

- In patients with a previous diagnosis of melanoma, clinical follow-up requires a thorough examination.

- A pigmented lesion in the oral cavity always suggests oral malignant melanoma. Any pigmented lesion of the oral cavity for which no direct cause can be found requires biopsy.

- Sentinel-node biopsy or lymphoscintigraphy, which is beneficial in staging of cutaneous melanoma, has little value in staging or treating oral melanoma. Complex drainage patterns may result in the bypass of some first-order nodes and in the occurrence of metastasis in contralateral nodes.

Histologic Findings:

Although any of the features of cutaneous malignancy can be found, most oral melanomas have characteristics of the acral lentiginous (mucosal lentiginous) and, occasionally, superficial spreading types.

The malignant cells often nest or cluster in groups in an organoid fashion; however, single cells can predominate. The melanoma cells have large nuclei, often with prominent nucleoli, and show nuclear pseudoinclusions due to nuclear membrane irregularity. The abundant cytoplasm may be uniformly eosinophilic or optically clear. Occasionally, the cells become spindled or neurotize in areas. This finding is interpreted as a more aggressive feature, compared with findings of the round or polygonal cell varieties. In the oral mucosa, the prognosis is dismal for patients with any type of malignant cell.

Melanomas have a number of histopathologic mimics, including poorly differentiated carcinomas and anaplastic large-cell lymphomas. Differentiation requires the use of immunohistochemical techniques to highlight intermediate filaments or antigens specific for a particular cell line.

Leukocyte common antigen and Ki-1 are used to identify the lymphocytic lesions. Cytokeratin markers, often cocktails of high- and low-molecular-weight cytokeratins, can be used to help in the identification of epithelial malignancies.

S-100 protein and homatropine methylbromide (HMB-45) antigen positivity are characteristic of, although not specific for, melanoma. S-100 protein is frequently used to highlight the spindled, more neural-appearing melanocytes, whereas HMB-45 is used to identify the round cells. Melanomas, unlike epithelial lesions, are identified by using vimentin, a marker of mesenchymal cells. Recently, microphthalmic transcription factor, tyrosinase, and melano-A immunostains have been used to highlight melanocytes. The inclusion of these stains in a panel of stains for melanoma may be beneficial.

Staging:

- The American Joint Committee on Cancer does not have published guidelines for the staging of oral malignant melanomas. Most practitioners use general clinical stages in the assessment of oral mucosal melanoma as follows:

- Stage I – Localized disease

- Stage II – Regional lymph node metastasis

- Stage III – Distant metastasis

- Tumor thickness and lymph node metastasis are reliable prognostic indicators.

- Lesions thinner than 0.75-mm rarely metastasize, but they do have the potential to do so. On occasion, a small primary lesion is discovered after a symptomatic lymph node is harvested.

Treatment

Medical Care:

Medical therapy is not often beneficial with oral melanoma.

- Drug therapy (dacarbazine), therapeutic radiation, and immunotherapy are used in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma, but they are of questionable benefit to patients with oral melanoma. Dacarbazine is not effective in the treatment of oral melanoma; however, dacarbazine administration in conjunction with interleukin-2 (IL-2) may have therapeutic value.

- Experience with oral malignant melanoma is largely derived from single cases. Anecdotal reports of success with interferon alfa (INF-A) or hyperfractionated radiation therapy exist.

- Many cancer centers follow surgical excision with a course of IL-2 as adjunctive therapy to prevent or limit recurrence.

- Because of the rarity of the lesions, assembling a cohort study group to evaluate the different therapeutic regimens is difficult. Hopefully, future research will incorporate standardized multimodal therapy, such as those used in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma.

Surgical Care:

- Electrodesiccation and cryosurgery are described as treatment modalities for early, superficial, palatal lesions. However, incomplete removal results in recurrence that may envelop the previous biopsy, excision, or treatment site and interfere with histologic evaluation. These methods have little or questionable benefit in the treatment of oral melanoma.

- Ablative surgery with tumor-free margins remains the treatment of choice. Early surgical intervention when local recurrence is detected enhances survival, because the dismal outcomes are associated with distant metastasis.

- About 80% of patients with oral melanoma have local disease, and 5-10% of patients present with grossly involved nodes.

- After complete surgical excision, the local-regional relapse rate is reported to be 10-20%, and 5-year survival rates are clustered around 10-25%, with a reported range of 4.5-48%. McKinnon et al report that tertiary care centers have the best results.

- Although radiation alone is reported to have questionable benefit (particularly in small fractionated doses), it is a valuable adjuvant in achieving relapse-free survival when high-fractionated doses are used.

- Eventually, multimodal therapy may be proven effective in the treatment of oral mucosal melanoma.

- Neither lymphoscintigraphy nor intraoperative blue-dye sentinel-node biopsy (eg, selective neck dissection) is useful in predicting drainage patterns in oral melanomas.

- Anatomic ambiguity appears to preclude consistent assessment of oral lymphatic drainage patterns when this technique is attempted.

- Surgical lymph node harvesting depends on the identification of positive nodes at clinical or imaging examination.

- Prophylactic neck dissection (ie, elective neck dissection) is not advocated as a treatment for oral melanoma.

Consultations:

- Consult the following specialists and facilitate their meeting during head and neck tumor boards to plan the best therapy and aftercare for patients with oral melanoma.

- Ear, nose, and throat surgeon

- Pathologist (eg, dermatopathologist and general surgical, head and neck, or oral and maxillofacial specialist)

- Medical and radiation oncologists

- Maxillofacial prosthodontists

- Speech therapist

- The primary concern is ensured surgical removal; secondary concerns deal with restoring function and cosmetic results. If the anatomy restricts ensured removal, medical oncologists and radiation oncologists must provide the most appropriate adjunctive therapy.

- Maxillofacial prosthodontists can provide advice about the appliances available and about tissue requirements for support and retention.

- The involved consultants should be aware of the recall schedule to assess patient progress and adaptation.

Diet:

-

Depending on the extent of surgery, dietary modifications may be necessary until obturators and dental appliances are fabricated and placed to restore function.

-

Chewing and deglutition may be severely compromised, and aspiration may be possible.

-

Retraining may be necessary to facilitate swallowing and to protect the swallowing reflex.

-

Nutritional counseling is helpful. Loss of teeth and significant bony anatomy make eating difficult. Soft diets are cariogenic and often high in fat and calories.

Activity:

- Most likely, surgery results in compromised oral function, which affects speech and nourishment. Rehabilitation and constant reinforcement may be important in restoring function.

- Nurse practitioners and dental personnel must encourage the patient to adopt healthy behaviors, and they must perform thorough examinations to rule out recurrence and to recognize and treat oral disease.

Medication

Chemotherapeutic medications for the treatment of oral melanoma do not reliably reduce tumor volume. Aggressive surgery remains the treatment of choice. Interferon, dacarbazine, and BCG have been tried with marginal and unpredictable results. New protocols with interferon (Intron A) and other immunotherapies are being investigated.

Multimodal therapy offers the best likelihood of relapse-free survival compared with any single therapy. Kirkwood et al showed that surgery followed by high-dose interferon alfa-2b in high-risk, cutaneous melanoma appears to be more beneficial than surgery followed by melanoma antigen vaccination. Although not evaluated in mucosal sites, these approaches may provide valuable adjuncts to the treatment of oral mucosal melanoma.

Follow-up

Further Inpatient Care:

- Diagnosis and subsequent surgical excision of oral melanoma require lifelong follow-up.

- Early discussions of potential problems with function, prostheses, oral fungal infection, and lesion recurrence may ensure patient compliance.

Further Outpatient Care:

- Periodic follow-up for oral examination and assessment is necessary to evaluate for recurrence. Perform a thorough oral examination and imaging studies regularly for the life of the patient. Recurrence is described as long as 11 years after the initial surgery.

- At follow-up visits, dental care, nutritional status, and difficulties with the prosthesis (if necessary) can be addressed. Patient comfort and function are assessed. Treatment or the follow-up schedule can be modified.

Deterrence/Prevention:

- No prevention strategies for oral malignant melanoma are known.

- Encourage patients to perform a thorough oral self-examination and to report abnormal findings to their dentist or physician.

- The most significant findings with self-examination are pigmentary changes; however, masses, ulcers, plaques, and altered sensation also are suggestive of malignant melanoma.

Complications:

- Complications stem from the loss of anatomic structure because of the surgical procedure.

- The loss can result in prolonged or compromised healing or the need for tissue grafting or prosthesis fabrication.

- Grafts can fail, and prostheses can irritate mucosa and supporting tissues.

- Xerostomia (ie, oral dryness), hypernasal speech, and increased incidence of oral fungal infections are possible effects of surgical treatment.

- INF-A use is associated with malaise, flulike symptoms, fever, and myalgia.

- Patient education and scheduled follow-up visits can minimize the postoperative complications.

Prognosis:

- The prognosis for patients with oral malignant melanoma is relatively dismal.

- Early recognition and treatment greatly improves the prognosis.

- Late discovery and diagnosis often indicate the existence of an extensive tumor with metastasis.

- After surgical ablation, recurrence and metastasis are frequent events, and most patients die of the disease in 2 years.

- A review of the literature indicates that the 5-year survival rate within a broad range of 4.5-48%, but a large cluster occurs at 10-25%.

- The best option for survival is the prevention of metastasis by surgical excising any recurrent tumor.

- Eneroth and Lundberg state that patients are not cured of oral melanoma and that the risk of death always exists. Long periods of remission may be punctuated by sudden and silent recurrence.

Patient Education:

- Teach the patient how to perform an effective oral examination.

- All oral mucosal surfaces available for inspection should be visualized.

- This examination requires a bit of dexterity and head movement to reflect light appropriately.

- Adequate oral examination requires good lighting, a mouth mirror, a bathroom

mirror, and a 2 X 2 gauze sponge. - The tongue is retracted and moved from side to side with the 2 x 2 gauze to achieve an unobstructed view.

- Healthcare practitioners can reinforce this practice at follow-up appointments and ask patients to demonstrate their skill.

Miscellaneous

Medical/Legal Pitfalls:

- Misdiagnosis and the failure to diagnose are most commonly associated with nonpigmented oral malignant melanomas.

- Clinically, a lesion may be mistaken for a benign pigmented lesion, a reactive process, or an anatomic variation.

- This mistake can be made especially when the examination is cursory or performed by healthcare providers who are unfamiliar with oral examination.

- The best advice is to perform a systematic and thorough examination.

- Histologically, amelanotic melanomas require the use of special stains because of the pathologic mimics. Appropriate immunohistochemical stains or panels can be used to distinguish possible considerations such as lymphoid, epithelial, and neuroendocrine lesions.

Special Concerns:

- Historically, oral malignant melanoma was reported to progress more rapidly in pregnant females for unknown reasons. This finding was refuted by Borden, who reiterated that the only reliable prognostic indicator is the stage of the disease at diagnosis and not pregnancy.

- Medical therapy and radiation therapy are necessarily curtailed during pregnancy; however, those treatments usually are not an issue in patients with oral malignant melanoma.

- Surgery during pregnancy is problematic because of the requirements for anesthesia and analgesics.

- The consideration of pregnancy termination or therapeutic abortion is not clearly justified. The decision must rest with the parents, obstetrician-gynecologist, and surgeon responsible for treating the malignancy.

Oral malignant melanoma pictures

Caption: Picture 1. Oral malignant melanoma. Man with an ulcerated, blue-black, slightly elevated lesion in the edentulous, posterior maxilla on the right side. The lesion extends across the residual alveolar ridge onto the palate and onto the facial aspect of the ridge. The diagnosis is oral melanoma. Courtesy of Dr Carl Allen, Ohio State University.

Caption: Picture 2. Oral malignant melanoma. Japanese male patient with extensive, black-pigmented and irregularly bordered macule in the maxillary labial mucosa and midline facial gingiva, (teeth 8 and 9). (The patient’s fingers are depicted.) The diagnosis is oral melanoma. Courtesy Dr Bob Goode, Tufts University.

Caption: Picture 3. Oral malignant melanoma. Large, blue-black, irregularly bordered lesion on the upper lip of a Japanese male patient. The diagnosis is oral melanoma. Courtesy Dr Bob Goode, Tufts University.

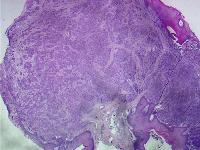

Caption: Picture 4. Oral malignant melanoma. A polypoid mass. Rounded collections or nests of melanocytes fill the connective tissue and have tropism for the surface epithelium (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification X2). This mass was excised from the lingual surface of the posterior mandible of an elderly man. The diagnosis is oral melanoma.

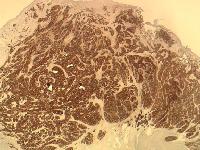

Caption: Picture 5. Oral malignant melanoma. A polypoid mass with tumor cells shows strong, positive staining with S-100 protein immunohistochemical stain (original magnification X2). The diagnosis is oral melanoma.

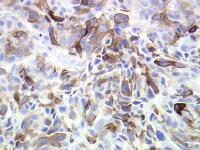

Caption: Picture 6. Oral malignant melanoma. Tumor cell cytoplasmic homatropine methylbromide (HMB-45) immunohistochemical staining (original magnification X40). The diagnosis is oral melanoma.

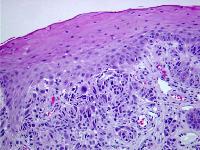

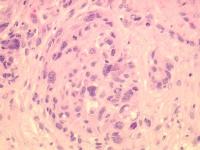

Caption: Picture 7. Oral malignant melanoma. Tumor cells show affinity for the surface epithelium (merging of tumor and epithelium). Cellular pleomorphism and smudged nuclei with pseudoinclusions are noted (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification X10). The diagnosis is oral melanoma.

Caption: Picture 8. Oral malignant melanoma. Rounded nest of various sized melanocytes with nuclear pseudoinclusions (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification X40). The diagnosis is oral melanoma.

Caption: Picture 9. Oral malignant melanoma. Two, diffusely bordered, dark gray macules in the left posterior buccal mucosa adjacent to molar teeth that have been restored. The diagnosis is an amalgam tattoo.

Caption: Picture 10. Oral malignant melanoma. Clinical photo of an irregularly shaped, tan-brown macule in the right side of the posterior hard palate. The diagnosis is oral melanotic macule.

Caption: Picture 11. Oral malignant melanoma. Clinical photo of the buccal mucosa of a middle-aged, black woman with a brown-black, irregularly bordered macule that arose suddenly. The patient was unaware of its presence. The diagnosis is oral melanoacanthoma.

Author Information

Author:

- Bobby Collins, DDS, Assistant Professor of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Department of Oral Medicine and Pathology, University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine. Dr Collins is a member of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology

Coauthor(s):

- John Abernethy, MD, Associate Professor, Departments of Dermatology and Pathology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center;

- Leon Barnes, MD, Professor, Department of Pathology,

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Editor(s):

- Peter Fritsch, MD, Chair, Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Innsbruck, Austria

- Michael J Wells, MD, Staff Physician, Department of Dermatology, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center

- Drore Eisen, MD, DDS, Consulting Staff, Department of Dermatology, Dermatology Research Associates of Cincinnati

- Joel M Gelfand, MD, MSCE, Assistant Professor, Department of Dermatology, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania Hospital

- William D James, MD, Program Director, Vice-Chair, Albert M Kligman Professor, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

2010 Update on new melanoma vaccine trials

BACKGROUND: Melanoma is the most serious type of skin cancer. It begins in skin cells called melanocytes, the cells that produce the color of our skin. The first sign of melanoma is often a change in the size, shape, or color of a mole. However, melanoma can also appear on the body as a new mole. According to the American Cancer Society, there were 68,700 news cases of melanoma in 2009 and more than 8,500 deaths.

In men, melanoma most often shows up on the upper body, between the shoulders and hips and on the head and neck. In women, it often develops on the lower legs. In dark-skinned people, melanoma often appears under the fingernails or toenails, on the palms of hands or on the soles of the feet. Although these are the most common places for melanomas to appear, they can appear anywhere on the skin including inside the oral cavity.

NEW VACCINE: A new vaccine is being tested around the country to treat advanced melanoma. It’s called OncoVEX (Talimogene laherparepvec). It’s currently having very positive results and is in the third phase of the study. In phase two, involving 50 patients with metastatic melanoma, eight recovered completely and four partially responded to the vaccine. The vaccine was initially developed to combat the herpes virus. Researchers discovered accidentally that the vaccine attacked cancerous tissue when it was inadvertently placed in a Petri dish of tumor cells. OncoVEX includes an oncolytic virus — a reprogrammed virus that has been converted into a cancer-fighting agent that attacks cancer and leaves healthy cells alone.