The son of parents who made ice cream on the Isle of Wight, off the coast of England, Mr. Minghella used expansive tastes in literature and a deep visual vocabulary to make lush films with complicated themes that found both audiences and accolades. Mr. Minghella’s films, which also included “Breaking and Entering” (2006), “The Talented Mr. Ripley” (1999) and “Cold Mountain” (2003), used a careful eye for cultural and historical detail to explore ways in which the dynamics of class often pushed people into corners that they had to fight or scheme their way out of.

His gift for building fully realized worlds within worlds also found expression in opera. Mr. Minghella directed an acclaimed staging of “Madama Butterfly” in 2006, and he was commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera to direct and write the libretto for a new work by the composer Osvaldo Golijov that was scheduled for the 2011-12 season.

Mr. Minghella recently completed work on “The No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency,” an adaptation of an Alexander McCall Smith novel, which was filmed in Botswana, in southern Africa, for HBO and the BBC as the pilot of a series.

He worked as a writer and a director in both theater and television. Samuel Beckett was a particular fascination; Mr. Minghella organized a star-studded tribute to Beckett in 2006.

After his movie-directing debut in “Truly Madly Deeply,” a made-for-television production that was released theatrically in 1990, Mr. Minghella went on to adapt a number of novels for a series of well-reviewed films. In addition to winning the directing Oscar in 1997 for “The English Patient” — which garnered a total of nine Oscars, including best picture — Mr. Minghella also received an adapted-screenplay nomination. In 2000 his screenplay for “The Talented Mr. Ripley” was nominated as well.

That same year Mr. Minghella joined a fellow director, Sydney Pollack, to form Mirage, an independent production company that concluded a three-year first-look deal with the Weinstein Company earlier this month. They collaborated as producers on a number of films and worked on each other’s films as well.

“He was interested in the magic,” Mr. Pollack said. “Not fake magic, like hiding the ball under the cup, but real magic, the kind that occurs between people. Nowadays, everybody making movies wants to get the clothes off fast and the guns out quick, he was just the opposite. He was interested in the poetry, lavishing the viewer with story, and scope and richness. Look at what you got for your $12 ticket with Anthony.”

“There was a real authenticity to his work,” Mr. Pollack added. “He made movies about the world that we live in, where stuff happened that no one could have anticipated.”

Mr. Minghella recently stepped down from his position as chairman of the British Film Institute, an organization that promotes making films in Britain.

Anthony Minghella was born on Jan. 6, 1954, and grew up on the Isle of Wight, where his parents, immigrants from Italy, ran an ice cream factory. An outsider even in his native land, Mr. Minghella took on large historical issues in his work, like the human consequences of epic warfare in “Cold Mountain,” about a soldier’s journey across an American landscape battered by the Civil War. Closer to home, his film “Breaking and Entering” examined the interlocking lives of thieves and their victims in today’s London, a place where he believed immigrants are less assimilated than tolerated.

“But while we share the geographical space, we don’t share much else,” he said to The New York Times in 2006 in talking about the film, which was based on his first original screenplay since “Truly Madly Deeply.” “We’re not particularly well integrated. One of the curiosities can be the differences, rather than the similarities, between people walking down the street — differences in expectation and privilege, in wealth and opportunity. It’s not tension or aggression, but a kind of guarded indifference. We coexist rather than create communities.”

Mr. Minghella’s concern with seeing beyond roles assigned by hierarchy or education extended to the work itself.

“Anthony was the opposite of the prissy, hysterical director,” said Peter Gelb, general manager of the Metropolitan Opera. “He was calm and intelligent and persuasive, whether he was talking to a board member or a member of the stage crew.”

In what was viewed as a risky move at the time, Mr. Gelb chose Mr. Minghella to direct “Madama Butterfly,” which opened the Met’s 2006 season. Although Mr. Minghella was a trained pianist, he was an opera neophyte before the “Butterfly” production, which originated at the English National Opera in London.

“Everyone here had every reason to be suspicious of him because they knew his opera credentials were limited,” Mr. Gelb said. ”But he set the tone at the first rehearsal — he told the people in the production that he wanted them to read the text to him before they sang a note. The message was clear, that they were not only opera singers, but actors as well.”

The subsequent production, which included blended cinematic elements (a series of movable screens) along with creative stagecraft (Cio-Cio-San’s son was rendered as a puppet) pleased critics and audiences alike.

Mr. Minghella is survived by his wife, Carolyn Choa, who choreographed the “Butterfly” production; his son, Max; his daughter, Hannah; his parents, Eddie and Gloria Minghella; his brother, Dominic; and three sisters: Gioia, Loretta and Edana.

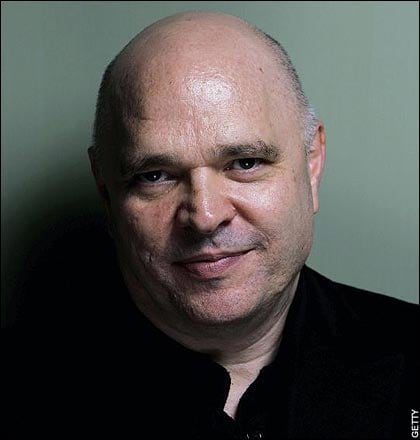

With a large, bald head, and a thick frame, Mr. Minghella had the physical affect of dockworker, but when he opened his mouth, it was clear he was an omnivorously literate person.

“I can’t think of a conversation that I had in the last five years that didn’t include a reference about what book he was reading,” said Scott Rudin, who produced a number of films with both Mr. Minghella and Mr. Pollack. “He was the first person to pick up the phone and talk about some amazing play he had seen in North London, and a few days later there would be a script on my desk.”

Mr. Pollack said the history of successful production collaborations between directors was so short as not worth measuring, but said that while he and Mr. Minghella often disagreed about particulars — “We fought plenty” — they had values in common.

“We both know what was junk and what was good,” Mr. Pollack said. “There were a lot of movies that we planned together and are now not going to be able to do. It’s sad for me, but it’s also too bad that people won’t see those movies.”

Mr. Minghella died from complications for surgery he had recently had for tonsil cancer, one of the locations generally referred to as oral cancer, the largest group of those cancers of the head and neck.

Story by NT Times