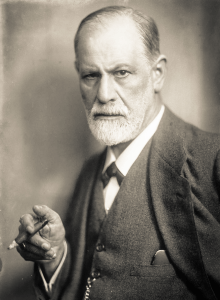

Sigmund Freud

Tobacco use is linked to the powerful addictive effect that nicotine can have on the body, causing oral, lung and throat cancers while making it very difficult for a person to stop using tobacco in whatever form. Knowing this addictive effect can have both physical and psychological elements, it is perhaps ironic that one of the most famous oral cancer sufferers of all was the father of modern psychoanalysis.

Sigmund Freud was born May 6, 1856, in Moravia. When he was very young, the family moved to Vienna, where he lived most of his life. In many ways he is considered to be the most important historical figure in the areas of psychology and psychiatry, and his theories on the subconscious are debated in these fields to this day. However, he suffered from a powerful mental and physical addiction to nicotine, which would ultimately lead to heart problems and a series of oral cancers that would end his life.

While we have much evidence of his addiction in the form of letters and journals, Freud was nearly always photographed with a cigar in hand. This is not really surprising, as he usually smoked 20 per day. When Freud was in his late 30’s, he began experiencing chest pains and shortness of breath. His physician/friend Wilhelm Fliess urged Freud to give up cigars, attributing his problems to excessive smoking and hypersensitivity to nicotine. Fliess’ warnings and the suggestion of a connection between his heavy smoking and poor health concerned Freud, but in spite of his anxiety, he kept smoking cigars at his regular rate throughout the day. Obviously Dr. Freud was not convinced that cigars were linked to his heart problems.

Frued learned no lesson from his early heart problems, and would not comply with any effort to modify his cigar smoking. In a letter to Fliess after being advised him not to smoke, Freud stated that he “… was deprived of the motivation which you so aptly characterize in one of your previous letters: a person can give something up only if he is firmly convinced that it is the cause of his illness . . .”

In 1923, when he was 67 years old, Freud’s cigar smoking began to produce outward indications of the painful cancer that would kill him. Freud developed a growth in his mouth that later turned out to be cancer of the soft palate. He was not a fool, after all Freud was a doctor himself, as were many of his closest friends. Nevertheless, he waited years before showing anyone the growth in his mouth. He feared that his cigar habit would rightly be blamed.

An operation was eventually performed — the first of thirty-three operations for cancer of the jaw and oral cavity which he endured during the sixteen remaining years of his life. “I am still out of work and cannot swallow,” he wrote shortly after this first operation. “Smoking is accused as the etiology of this tissue rebellion.” At the advanced stages of his long disease he had to use a special prosthesis, which covered the defect in his palate. He called this prosthetic appliance “the monster”.

In addition to his series of cancers and cancer operations, all in the oral area, Freud now regularly suffered attacks of “tobacco angina”, or heart palpitations, whenever he smoked. He tried partially denicotinized cigars (an early attempt at making smoking safer), but even these produced anginal pains and other heart symptoms.

At seventy-three, Freud was ordered to retire to a sanitarium for his heart condition. And Freud did stop smoking. . .for twenty-three days. Then he started smoking one cigar a day, then two. Soon his habit was as strong as ever.

In 1936, at the age of seventy-nine, and in the midst of his endless series of mouth and jaw operations for cancer, Freud had more heart trouble.

“It was evidently exacerbated by nicotine,” one doctor wrote, “since it was relieved as soon as he stopped smoking.” Freud’s jaw had by then been entirely removed and several artificial pieces substituted; he was in almost constant pain; often he could not speak and sometimes he could not chew or swallow. Yet at the age of eighty-one, Freud was still smoking – every day, all day.

He worked and smoked up to the very end of his life at age 83. One of the last photographs taken of Freud in the year prior to his death shows the psychoanalyst sitting at his desk at 20 Maresfield Gardens in London, where he moved after escaping Nazi-occupied Austria in 1938. The 82 year old Freud was dressed in full suit and tie, and yes, he had a cigar in hand.

Why did Freud continue to smoke, in the face of such grave medical procedures and with such strong evidence linking his cigars to his ill health?

During one period of abstinence urged by Dr. Fliess, Freud wrote in a letter to him: “I have not smoked for seven weeks since the day of your injunction. At first I felt, as expected, outrageously bad. Cardiac symptoms accompanied by mild depression, as well as the horrible misery of abstinence. These wore off but left me completely incapable of working, a beaten man. After seven weeks I began smoking again…Since the first few cigars, I was able to work and was the master of my mood; before that life was unbearable.”

Anybody who has tried and failed to quit smoking will recognize this chain of logic. After all, how could Fliess insist that Freud stop smoking forever after hearing of the positive effect cigars had on Freud’s mood? The most interesting thing about this, is that Freud pioneered our understanding of the way people employ psychological defense mechanisms when faced with intolerable thoughts and feelings; at the same time, he was a master of such defense mechanisms.

Freud died of oral cancer in 1939, at the age of eighty-three. The last fifteen years of his life were a series of nicotine withdrawal symptoms, heart palpitations, painful, dangerous surgeries, and the replacement of most of his jaw with painful, inefficient substitutes.

He smoked until the end.