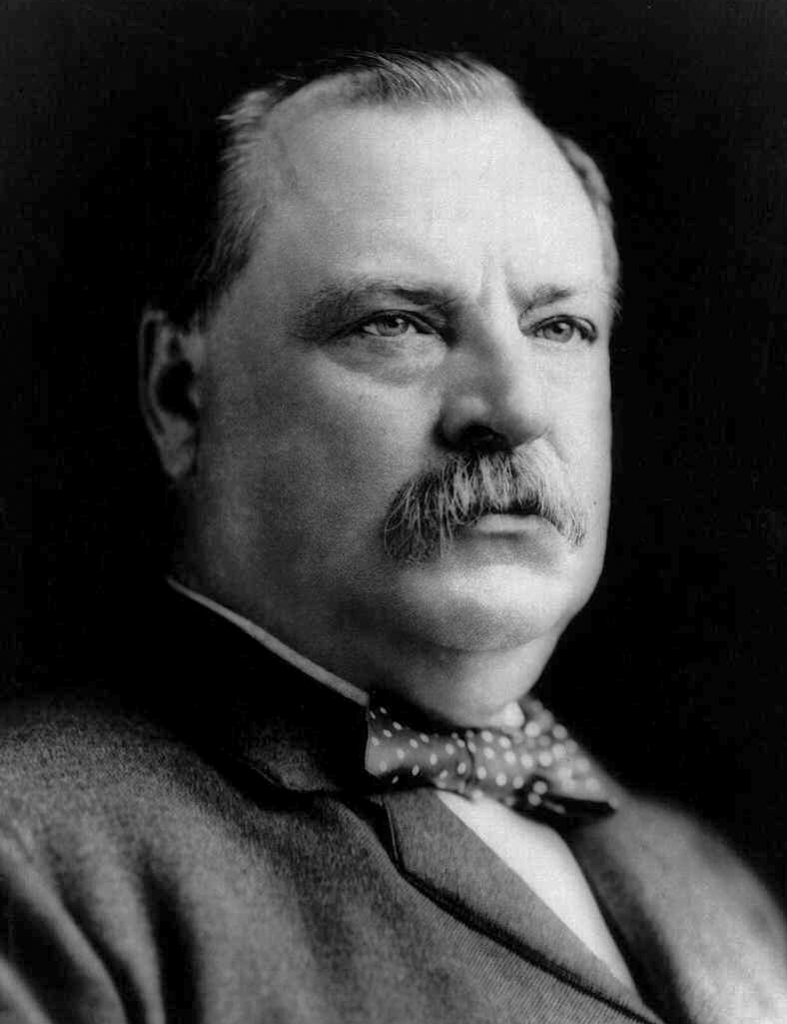

Grover Cleveland

Alcohol, tobacco, and a president

The patient was an overweight cigar smoker with a penchant for alcohol who one day noticed a swelling on the roof of his mouth but chose not to tell anyone about it for several weeks. When doctors were called in and pressed for a diagnosis, the verdict was cancer.

The year was 1893, a time of serious political and economic turmoil. The patient was Grover Cleveland, formerly 22nd and then 24th president of the United States. Cleveland, who had been haunted by fear of cancer and panicked at the diagnosis, set upon an elaborate scheme to keep the truth from virtually everyone, including some of the physicians who would treat him.

He contrived to spend the Fourth of July holiday aboard the yacht Oneida, setting sail from New York City and leisurely traveling to his summer home in Massachusetts. En route, doctors would remove his cancer. Preparations were as meticulous as possible under the circumstances. Physicians, dentists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists were sworn to secrecy; some didn’t know the identity of the patient until the Oneida was en route. On July 1, 1893, as the yacht steamed at half speed, the salon was converted into a crude operating room. The setup included oxygen, nitrous oxide, ether, two storage batteries to power cautery instruments and lights, strychnine in case of shock, digitalis, and morphine. Shortly after noon, the president, who had had toast and coffee for breakfast, walked to the makeshift operating room and sat in a chair lashed to the interior mast. Some accounts say the ship’s steward served as the surgical nurse.

The operation itself was a masterpiece for its time, although details were not reported until years later. Using far more anesthesia than surgeons anticipated, the team removed a major part of Cleveland’s left upper jaw, leaving a defect 2 1/2 inches long from front to back and almost 1 inch wide. The procedure was a nightmare for the medical team, but the recovery was remarkably uneventful, and the president was up and about in a few days. He couldn’t eat normally or talk until some weeks later when a specialist fashioned a rubber prosthesis to fill the hole in his mouth.

The press did get wind of the operation, possibly through a naive dentist who was brought on board to help with the anesthesia and later told his associates why he was late for work. Within a week, several newspapers reported that the president had had a malignant growth removed. At that time, cancer was greatly misunderstood; it was still considered by some to be a “social disease” – not what the President of the United States wanted to be remembered for. The spin doctors of that era were up to the task, however. What followed was a masterful medical disinformation ploy designed to move the press away from the truth. “The president had some dental work done and also is suffering from rheumatism,” his doctors reported.

Grover Cleveland lived another 16 years, suggesting that the cancer was not nearly as lethal as his doctors suspected. Nonetheless, the secret surgery set a precedent that held for many decades thereafter.

Hiram Ulysses Grant

Soldier, President

Following this man through his life, you would have never thought he would one day be the Eighteenth President of the United States. Hiram Ulysses Grant, or Ulysses S. Grant as he is more commonly known, led a life full of successes and failures. Far from remarkable in his early life, Grant made it through early hardship and lackluster performance to lead the entire Northern Army in the Civil War, and found success in politics. But after he achieved the most powerful position in the America, Grant was stricken with oral cancer, and suffered terribly before he finally fell victim to the disease. He remains the only President of the United States to die of cancer. Years of cigar smoking and periods of heavy drinking were probably to blame.

Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio on April 27, 1822 to parents Jesse and Hannah. His father owned a tanning business and Grant had many advantages as a child. He went to grammar school at Marysville Seminary and then attended the Presbyterian Academy in Ripley, Ohio. In neither of these institutions did Grant show any scholarly aptitude or desire. But to his credit he was an excellent horseman and was able to ride even the wildest horses. Despite his lackluster scholasticism, Grant’s father was able to get him an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Grant’s career at the academy seemed destined for mediocrity right from the outset. The congressman who nominated Grant for the academy had spelled his name as Ulysses S. Grant and this name was officially listed in the registry. Grant tried many times to have his proper name listed but was unsuccessful. He eventually gave up and adopted the new name as his own. Grant, wholly uninterested in education, was not very enthusiastic about going to West Point. “A military life had no charms for me,” he later wrote in his journal. He merely wanted to “to get through the course, secure a detail for a few years as assistant professor of mathematics at the Academy, and afterwards obtain a permanent position as professor at some respectable college.”

His lack of enthusiasm for the academy was apparent in his performance. He graduated in 1843, ranked 21st out of 39 students, and again, only excelled in horsemanship. Upon graduation he was assigned to the 4th Infantry in St. Louis as regimental quartermaster during the Mexican War. Under the command of Zachary Taylor, he frequently led companies into battle. The Mexican War was the first time Grant distinguished himself in battle, and he received brevets for his bravery. Once the Mexican War was over, Grant was transferred to the West Coast and had to leave new wife Julia Dent, whom he met while serving in the infantry, at home.

These years were to be hard on Grant. He did not get along with his superior officers, and his business ventures, through which he attempted to raise money to bring Julia out to the coast with him, failed. Grant was miserable. The more leisurely pace of peacetime allowed Grant to drink and smoke much more often than any time during the Mexican War. He later admitted that during this time he smoked up to 12 cigars a day. In July of 1854, Grant, amid rumors of disciplinary action for his drinking and behavior, resigned his commission to move home to his wife. He settled on 80 acres of family farmland with Julia.

But civilian life treated him no better than military life. Although he had his wife, he was unsuccessful at maintaining the farm. Grant then failed at attempts to secure jobs as an engineer and a clerk in St. Louis. He also tried to set up a real estate business, but that failed also. He ended up working as a clerk in his family’s leather goods store in Galena, Ohio. He was working there when the Civil War broke out, and he was off to war again.

Once the war was official, Grant was quick to offer his services to the US Government. He was unable to attain an appointment, so he organized a volunteer company in his home of Galena. Grant quickly ascended the ranks and made a name for himself in the Battle of Fort Henry. Union troops under Grant attacked the fort and forced Confederate General Simon Buckner to surrender. When Buckner asked for the terms of surrender, Grant told him there were no terms but an unconditional and immediate surrender. This earned him the nickname of “Unconditional Surrender” Grant. Grant eventually became commander of the Northern Army and helped the Union defeat the South. These times during the war saw his drinking and smoking habits continue with the victories and defeats of the many battles he oversaw.

After the war Grant was appointed to full general and was to oversee the rebuilding of the South. In 1867 President Johnson suspended Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and assigned Grant as interim secretary. But when the Senate refused to agree with the suspension, Grant resigned from the position, against President Johnson’s wishes. President Johnson’s unkind comments about Grant led him to join the Republican Party, which made him their nominee for President. He easily defeated Horatio Seymour in the presidential election and took office in 1868.

Grant’s Presidency was marred with scandals and problems. With regard to the South, Grant tried to assert the rights of African Americans, but the power of the Klu Klux Klan was too much for Grant to deal with. His efforts to enforce the 14th and 15th amendments failed miserably. Relations with American Indians proved no better, and despite his attempts to make peace with the Indians, Custer’s actions destroyed Grant’s efforts. There were also both railroad and Senate pay scandals that marred his administration. But despite all these problems, Grant served as President for two terms and none of problems were ever directly linked to or blamed on him. He left office with a good reputation, even though his two terms were not that wonderful.

His years after office proved to be toughest on him. Financially, a number of unsuccessful business ventures left him with little money. He then became a partner in the Grant & Ward brokerage firm, which went bankrupt and left Grant penniless. He was so destitute that had to sell wartime souvenirs and swords to keep afloat. The government later voted to reassign him the title of general so he could again have a salary, but he would have little time to enjoy the money because of his failing health. He began his autobiography, in which he was aided by, and finally published, with the help of Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain).

The first sign of cancer came in 1884 when Grant’s wife recalled, “there was a plate of delicious peaches on the table, of which the General was very fond. Helping himself, he proceeded to eat the dainty morsel; then he started up as if in great pain and exclaimed, ‘Oh my. I think something has stung me from that peach.'” Grant did not think anything was wrong, and did not report the pain to a doctor. Soon, the “sting” had grown into carcinoma of the right tonsular pillar, and Grant began to suffer. By the time Grant consulted his doctor the oral cancer was untreatable. The only treatment available at the time was an application of cocaine hydrochlorate solution to the cancerous area, which only helped suppress the pain. Grant suffered a slow, painful death, but he endured it with great courage. Once news of his oral cancer got out, reporters lined the streets outside his house and wrote daily reports about the beloved ex-President.

Here is an excerpt from one such article taken from the New York Times on March 29, 1885:

After Dr. Douglas left General Grant last evening the patient sufferer did not fall asleep. He lay quietly for an hour or two, when his breathing suddenly became difficult. His servants gave him a glass of water in the hope of affording him some relief, but the effort at swallowing was unsuccessful, and resulted in choking the patient, whose coughing fit became so violent as to alarm Colonel Grant. A carriage was dispatched in haste for Dr. Douglas and Dr. Shrady. The members of the family were also summoned to the General’s room. The throat trouble had become painful and alarming. The physicians reached the house shortly after two o’clock. They stayed with the General until the early dawn hours. The General’s throat was cleared and the fit of coughing checked.

Grant finally died on July 23, 1885.