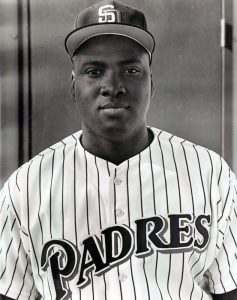

Tony Gwynn

Tony Gwynn, the Hall of Famer with a sweet left-handed swing who spent his entire 20-year career with the Padres and was one of the game’s greatest hitters, died of cancer Monday. He was 54.

Tony Gwynn, the Hall of Famer with a sweet left-handed swing who spent his entire 20-year career with the Padres and was one of the game’s greatest hitters, died of cancer Monday. He was 54.

Gwynn, a craftsman at the plate and winner of eight batting titles, was nicknamed “Mr. Padre” and was one of the most beloved athletes in San Diego.

He attributed his oral cancer to years of chewing tobacco. He had been on a medical leave since late March from his job as baseball coach at San Diego State, his alma mater. He died at a hospital in suburban Poway, agent John Boggs said.

“He was in a tough battle and the thing I can critique is he’s definitely in a better place,” Boggs told The Associated Press. “He suffered a lot. He battled. That’s probably the best way I can describe his fight against this illness he had, and he was courageous until the end.”

In a rarity in pro sports, Gwynn played his whole career with the Padres, choosing to stay rather than leaving for bigger paychecks elsewhere. His terrific hand-eye coordination made him one of the game’s greatest contact hitters. He had 3,141 hits, a career .338 average and won eight NL batting titles. He excelled at hitting singles the other way, through the “5.5 hole” between third base and shortstop.

Gwynn’s wife, Alicia, and other family members were at his side when he died, Boggs said.

Gwynn’s son, Tony Jr., was in Philadelphia, where he plays for the Phillies.

“Today I lost my Dad, my best friend and my mentor,” Gwynn Jr. tweeted. “I’m gonna miss u so much pops. I’m gonna do everything in my power to continue to … Make u proud!”

Gwynn had two operations for cancer in his right cheek between August 2010 and February 2012. The second surgery was complicated, with surgeons removing a facial nerve because it was intertwined with a tumor inside his right cheek. They grafted a nerve from Gwynn’s neck to help him eventually regain facial movement.

Gwynn had said he believed the cancer was from chewing tobacco.

Gwynn had been in and out of the hospital and had spent time in a rehab facility, Boggs said.

“For more than 30 years, Tony Gwynn was a source of universal goodwill in the national pastime, and he will be deeply missed by the many people he touched,” Commissioner Bud Selig said.

Gwynn was last with his San Diego State team on March 25 before beginning a leave of absence. His Aztecs rallied around a Gwynn bobblehead doll they would set near the bat rack during games, winning the Mountain West Conference tournament and advancing to the NCAA regionals.

Last week, SDSU announced it was extending Gwynn’s contract one season.

San Francisco Giants third base coach Tim Flannery, who played with Gwynn and then coached him with the Padres, said he’ll “remember the cackle to his laugh. He was always laughing, always talking, always happy.”

“The baseball world is going to miss one of the greats, and the world itself is going to miss one of the great men of mankind,” Flannery said. “He cared so much for other people. He had a work ethic unlike anybody else, and had a childlike demeanor of playing the game just because he loved it so much.”

Gwynn played in the Padres’ only two World Series and was a 15-time All-Star.

He homered off the facade at Yankee Stadium off San Diego native David Wells in Game 1 of the 1998 World Series and scored the winning run in the 1994 All-Star Game. He was hitting .394 when a players’ strike ended the 1994 season, denying him a shot at becoming the first player to hit .400 since San Diego native Ted Williams hit .406 in 1941.

Gwynn befriended Williams and the two loved to talk about hitting. Gwynn steadied Williams when he threw out the ceremonial first pitch before the 1999 All-Star Game at Boston’s Fenway Park.

Gwynn retired after the 2001 season. He and Cal Ripken Jr. — who spent his entire career with the Baltimore Orioles — were inducted into the Hall of Fame in the class of 2007. A wreath was being placed around his plaque in the Hall of Fame on Monday.

Also in 2007, the Padres unveiled a bronze statue of Gwynn on a grassy hill just beyond the outfield wall at Petco Park. While Gwynn was still with the Padres, then-owner John Moores donated $4 million to San Diego State for a new baseball stadium that bears the Hall of Famer’s name.

Gwynn was a two-sport star at San Diego State in the late 1970s and early 1980s, playing point guard for the basketball team — he still holds the game, season and career record for assists — and outfielder for the baseball team.

Gwynn always wanted to play in the NBA, until realizing during his final year at San Diego State that baseball would be the ticket to the pros.

“I had no idea that all the things in my career were going to happen,” he said shortly before being inducted into the Hall of Fame. “I sure didn’t see it. I just know the good Lord blessed me with ability, blessed me with good eyesight and a good pair of hands, and then I worked at the rest.”

He was a third-round draft pick of the Padres in 1981.

After spending parts of just two seasons in the minor leagues, he made his big league debut on July 19, 1982. Gwynn had two hits that night, including a double, against the Philadelphia Phillies. After doubling, Pete Rose, who had been trailing the play, said to Gwynn: “Hey, kid, what are you trying to do, catch me in one night?”

Gwynn also is survived by a daughter, Anisha.

AP

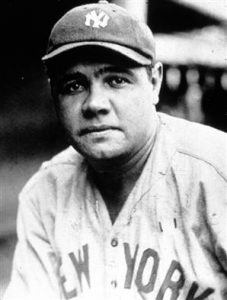

Babe Ruth

Jordan the “Babe Ruth of basketball,” or Wayne Gretzky the “Babe Ruth of hockey.” His name did not mean baseball, it meant greatness. He was a great player, and a great man. He had faults, like everyone else, but his faults were accepted because of his great qualities. He drank, womanized, smoked, and indulged in the good life. He also went out of his way to help children and was generous with his money. But his bad habits caught up with him and oral cancer cut his remarkable life short, sending a nation into mourning.

Jordan the “Babe Ruth of basketball,” or Wayne Gretzky the “Babe Ruth of hockey.” His name did not mean baseball, it meant greatness. He was a great player, and a great man. He had faults, like everyone else, but his faults were accepted because of his great qualities. He drank, womanized, smoked, and indulged in the good life. He also went out of his way to help children and was generous with his money. But his bad habits caught up with him and oral cancer cut his remarkable life short, sending a nation into mourning.

He was the greatest crowd pleaser of them all”

– Waite Hoyt, former teammate

Babe Ruth was born on February 6, 1895, in Baltimore, Maryland. He was the first child of George and Kate Ruth, and one of the eight children in the Ruth family. Tragically, he and his younger sister Marie were the only children to make it out of infancy and live an adult life. This is just one of many hardships Ruth endured through childhood. The Babe’s parents worked long hours in a tavern and did not give him much love or attention. With no one to watch him, Ruth was left to wander the dirty, crowded streets of the Baltimore riverfront. During this time Ruth picked up many bad habits that would come back to haunt him later. He was skipping school, stealing, chewing tobacco, and drinking his father’s whiskey. He once told a reporter,

I learned early to drink beer, wine, whiskey, and I think I was about five when I first chewed tobacco. There was a lot of cussin’ in Pop’s saloon, so I learned a lot of swear words, some really bad ones.

Finally his parents sent him to St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys because they no longer had time for him.

St. Mary’s was an orphanage and a reformatory that housed 800 boys. There was a huge wall that surrounded St. Mary’s and it looked more like a prison than an orphanage. Life got no better for Ruth during his first years at St. Mary’s. The other kids constantly teased Ruth and called him vulgar names. Administrators, who were very hard on him, also labeled him “incorrigible.” He was returned to his parents a few times to try to live with them but always ended up back at St. Mary’s.

One good thing did come out of his time at St. Mary’s, and his name was Brother Mathias. Mathias was the head disciplinarian at the school, so in the early days he and Ruth met with each other often. A relationship formed and Brother Mathias became a positive influence for Ruth. Ruth and Brother Mathias became so close that Ruth’s parents signed over custody of Babe to Mathias. Mathias assumed a father-figure relationship with Ruth and helped him reform his ways. He also introduced Ruth to a game called baseball.

It was in baseball that Ruth excelled. He was the best player in the school, and he could play all positions in the field. He was also an incredible hitter. He was so good that by the age of ten he was playing on the school’s varsity team, which was made up of fifteen and sixteen year-olds. When Ruth was nineteen years old, Jack Dunn, the manager of the minor league Baltimore Orioles, came to scout Ruth. He was so impressed with the young man’s skills that he signed him to a major league contract. To get Ruth on the team, Dunn also had to assume legal guardianship of Ruth from Brother Mathias because Ruth could not leave the school before he was twenty-one years old. Dunn was known for bringing in young talent, and upon arrival at training camp with Ruth one of the players joked, “here’s Jack’s newest babe.” The players began calling Ruth “Babe,” and the famous nickname stuck. Barely a week after being with the team, Ruth hit his first home run.

After five months with the Orioles, Ruth was sold to the Boston Red Sox in 1914 and became a major-leaguer. He came to the Red Sox as a pitcher, but he quickly showed his prowess as a hitter. Ruth helped the Sox win three world championships in the five years he was with the team. He won numerous games as a pitcher and led the major leagues with a 1.75 era in 1916. In 1919, Manager Ed Barrow put Ruth in the outfield, and he hit .322 with 29 home runs and 114 RBIs. Nobody had ever hits many home runs before. But at the end of the 1919 season, Ruth was traded to the New York Yankees for $125,000.00. The Red Sox have not won a World Series since Babe left.

His first year in New York saw the Babe hit 54 home runs. The next year, 1921, he hit 59 home runs and batted .377. The Yankees won six pennants and three World Series in eight years with Ruth on the team. Illness, suspensions, and bad habits left Ruth with a down year in 1922 and he only hit 35 home runs, but in 1923, Ruth made a tremendous comeback.The Yankees opened a new stadium that year, and Ruth hit a home run on opening day, one of 41 he would hit that year while batting .393. In 1927, Ruth did the impossible and hit 60 home runs, which was one eighth of the home runs in the league that year. But his off-field habits would come back and strangle his career.

On the field, Ruth was a god. At his time baseball had suffered the infamous Black Sox scandal, in which the White Sox had fixed the World Series. Also, during this time, baseball was low scoring and played defensively. Good pitching was emphasized and only a few runs were needed to win games. Then Ruth came and made hitting popular. He made the home run king. His ability to hit towering home runs enthralled the crowd and brought an excitement to baseball never seen before. Fans were drawn to Ruth because he could win games with one swing of the bat. His feats were the stuff of legends, such as his called shot in 1932. Whether this really happened or not is still debated. But he did call at least three shots. While playing for the Yankees in the 1928 World Series in St. Louis, Ruth was “booed cheerfully” by Cardinal fans as he trotted to left field to take his position. He grinned playfully and pointed beyond the right field wall, indicating the destination of his forthcoming hit. In three at bats he hit three home runs over this wall. He revived the game of baseball and easily became the most popular figure in the sport.

During his time with the Yankees, Ruth saw his salary increase dramatically. He went from making $10,000 with the Red Sox to making $80,000 with the Yankees. This salary was more than President Hoover made. When informed of this, he told reporters, “but I had a better year than Hoover.” With his money, Babe indulged in the high life. He stayed in a twelve-room suite at the Ansonia Hotel, the plushest hotel in New York, and was constantly carousing and spending loads of money. He drank heavily and was a favorite at bawd houses and bars across the country. He once broke a batting slump by staying out all-night and partying, and in the game the next day he hit two home runs. Teammates said he would eat half a dozen hot dogs and as many beers at a time. He even owned his own cigar company that manufactured Babe Ruth cigars, with his picture on the wrapper of each one. His weight ballooned during this time. With the Red Sox, he was a 6’2″, 175-pound athlete that can run all day. With the Yankees, his weight got up to 220 pounds from the effects of his constant partying.

Even though he partied quite a bit, the fans still adored him. Because of his rough childhood, Ruth had a soft spot for kids, and there was nothing he wouldn’t do for them. He was constantly visiting children in orphanages and hospitals, and he never refused a request or visit to help kids. He also never refused to sign an autograph, and encouraged kids to flock around him. After a World Series game while he was with Boston, Ruth went and played baseball with some kids in a sandlot.

Things like this made fans adore the Babe, and people looked past his indulgent lifestyle. He loved to spend money, and he was always giving to others. He would tip waiters $10, which was what most people made in one day of work. One time he found out that the hotel he was staying in did not have a piano, so he bought the hotel a piano and had it delivered while he was still there. He also bought Brother Mathias a new car.

The indulgent lifestyle may have been overlooked, but it soon caught up with him. His heavy drinking and smoking affected his career, and just before retiring he was diagnosed with nasopharyngeal carcinoma, which is cancer of the upper throat. Alcohol and tobacco in combination are the primary causative factors in this disease. Doctors performed surgery and gave him radiation treatments, but the treatments were unsuccessful. Ruth was released from the hospital in 1947 and allowed to go home and live out his last days. The cancer had metastasized and there was nothing doctors could do for him. In 1948 the Yankees celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of Yankee Stadium, “The House That Ruth Built.” The Babe attended the event, but he looked like a shadow of the man he once was.

In the celebration of the anniversary, members of the Ruth’s 1923 team played an exhibition against veterans from other years. Ruth was too frail and sick to take part in the festivities. Friends had to help him into his old uniform, which hung on his body like a tent. When Ruth was announced to the crowd to come on the field, he received a thunderous ovation. Ruth had to use a bat as a cane to walk out to home base. He got in front of the microphone to speak, and his voice was but a little rasp because the cancer had damaged his larynx. In his last speech, he told the crowd,

Thank you very much ladies and gentlemen. You know how bad my voice sounds. Well, it feels just as bad.

Later, sitting in the locker room, Joe Dugan came up with a beer for Ruth and asked him how things were. “Joe, I’m gone,” he said, and he began to cry. Later that year Ruth would die at the age of fifty-three. During his viewing, 100,000 fans came to Yankee stadium to pay their respect to Ruth, and men held up their kids to get one last look at Ruth. This was the sad end for the legendary man.

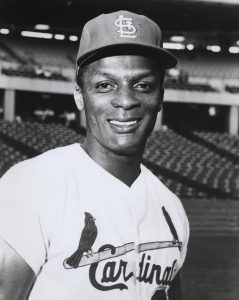

Curt Flood

Can there be a $90,000 a year slave? Curt Flood thought so, and his epic battle against major league baseball paved the way for what is the prosperous free agent market that so many baseball players enjoy today. This same market that is taken for granted today cost Flood his major league career and, at the time, gave him a bad reputation in the eyes of Americans. And though American opinion about Flood has reversed over time, his funeral after he succumbed to throat cancer in 1997 drew no attendance from current major leaguers who benefit from the sacrifices Flood made.

Can there be a $90,000 a year slave? Curt Flood thought so, and his epic battle against major league baseball paved the way for what is the prosperous free agent market that so many baseball players enjoy today. This same market that is taken for granted today cost Flood his major league career and, at the time, gave him a bad reputation in the eyes of Americans. And though American opinion about Flood has reversed over time, his funeral after he succumbed to throat cancer in 1997 drew no attendance from current major leaguers who benefit from the sacrifices Flood made.

Curt Flood was born in 1948 to a poor family in Houston, Texas. One of six children in the Flood family, Curt faced the danger of falling into a life of crime like older brother Carl or most of his friends. But after he stole a truck and crashed it, Curt realized the stupidity of his actions and began to concentrate on baseball and art as a way to avoid trouble and keep himself clean. And he excelled in both. Very athletic, Flood managed to escape poverty and find a career in baseball. At only 5′ 7′ and 140 pounds, the odds did not seem in Flood’s favor to succeed. But his determination made up for what his physique lacked.

When Flood first decided to pursue a baseball career, friends and coaches warned him not to get his hopes up. He had two things against him: he was small and he was black. But in 1956, after high school, Flood signed a contract for $4,000 with the Cincinnati Reds Organization. His first team was one of the Red’s minor league teams located in the South, and Flood experienced severe racism as well as a lack of confidence from his coaches. Not much was thought of the scrawny boy. But by the end of his first season, Flood had batted .340 and hit 29 home runs and even saw some major league action with the Reds. He thought the good season would bring him more money and a shot at the big leagues, but he was given the same pay next year and was not promoted to a higher team in the organization. The following year brought the same disappointment: a good season but no appreciation from management. It was at the end of the season that Flood also learned that he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals.

With the St. Louis Cardinals, Flood’s career took off. The decade of the sixties saw Flood become one of the best players in that era of baseball. He quickly piled up awards and records. He was one of the most consistent hitters in the sixties and hit over .300 six times. In 1964 he lead the league in hits with 211. As good a hitter as he was, he was an even better fielder. In 1968 Sports Illustrated put him on the cover with a caption reading “The Best Centerfielder in Baseball,” pronouncing him better than Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente. He won the Gold Glove Award seven times and set Major League records of 226 consecutive games without an error and 396 chances without an error. His team also took off, winning three pennants and two World Series titles. The sixties saw Flood hit his peak. But at the end of the decade he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies.

Flood was happy in St. Louis. He was a team captain and he was producing big numbers. When he was told he was traded to the Phillies, he was less than excited about the deal. “I was leaving one of the greatest organizations in the world at the time for what was probably one of the least liked.” To Flood, Philadelphia was the “northernmost southern city” and he had no intention of playing there. He decided he would fight the trade.

Up to this time, Major League baseball contracts had a reserve clause set in them. The reserve clause was that part of the standard player’s contract which bound the player, one year at a time, in perpetuity to the club owning his contract. Flood saw this part of the contract as a violation of his thirteenth amendment rights barring slavery and involuntary servitude. He decided to take Major League baseball to court and challenge the reserve clause. He wrote a now famous letter to then Commissioner Bowie Kuhn to state his position.

After twelve years in the Major Leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the sovereign States. It is my desire to play baseball in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia Club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decisions. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League Clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.

Flood then sat out the 1970 season and took his case to court. Kuhn v. Flood went all the way to the Supreme Court. Flood’s lawyer, former Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, argued that the reserve clause violated anti-trust laws by depressing wages and limiting a player to one team. The attorneys for Major League baseball argued the clause was a tradition and was for the good of the game. In a 5-3 decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Major League baseball, saying that baseball was exempt from anti-trust statutes. Later, in 1975, the court reversed its decision and free agency as it is known today was set in motion. But this did not help Flood, who lost his career and large amount of money in his trial. He sat out the 1970 season while his trial was being settled. He then signed with the Washington Senators in 1971 but retired after only thirteen games.

Flood not only lost money, but he also lost favor with America during the trial. Many could not believe Flood’s audacity and slandered him in newspaper articles for taking on baseball. It is only many years later that public opinion has turned to side with Flood and what his stand accomplished. Now Flood is seen as a hero and patriot for his efforts to give the player a right to have a say in whom he plays for, and how much he makes.

After he retired from the Washington Senators, Flood spent the next years in Europe running a tavern in Majorca, Spain. Here he picked up a drinking habit that he battled with for many years before finally beating it in 1978. The drinking, along with his cigarette habit, likely were the contributing factors which produced a diagnosis of inoperable throat cancer. It was after this diagnosis that baseball finally showed Flood some respect when the Baseball Player’s Association paid the medical bills for the last year of Flood’s life. Curt spent many months before his death at the UCLA Medical Center fighting his cancer, but on January 20, 1997, Flood lost his battle and died of pneumonia. At the funeral, Tito Fuentes wondered why none of the current players came to pay their respect. He said, “I’m sorry that so many of the young players who made millions, who benefited from his fight, are not here. They should be here.”

Off the field, Flood was as great a man as he was a player on it. He co-founded the Aunts and Uncles Organization with Cardinal lineman Ernie McMillan, which saw to it that all kids in the city of St. Louis had shoes to wear. He was also a talented artist, and his portraits are hanging in museums and in the houses of such people as August Busch IV, and the widow of Martin Luther King, Jr. After a brief stint as the color analyst for the Oakland A’s, Flood spent much of his time running a home for disadvantaged youth in Los Angeles. Of all the millionaires Curt Flood helped make, when Flood succumbed to cancer last January, not a single contemporary player attended his funeral. Not Shaquille O’Neal, he of the $110 million free-agent contract with the Los Angeles Lakers. Not Chad Brown, of the $24 million free-agent contract with the Seattle Seahawks. Not Albert Belle of the more than $50 million free-agent contract with the Chicago White Sox. Not anyone. Sadly, Flood experienced in death the kind of neglect and solitude he once knew in life.

Brett Butler

A Holy Hitter

Brett Butler has overcome many obstacles in his life. On the baseball field, Butler succeeded where he should have failed. Considered too slow and not talented enough to make it to the big leagues, Butler proved skeptics wrong and had a brilliant career in Major League Baseball. Even more important, off the field Brett Butler won a battle for his life. Butler overcame life threatening oral cancer and not only successfully returned to the field to finish his career, but also successfully influenced others to quit using tobacco.

Brett Butler has overcome many obstacles in his life. On the baseball field, Butler succeeded where he should have failed. Considered too slow and not talented enough to make it to the big leagues, Butler proved skeptics wrong and had a brilliant career in Major League Baseball. Even more important, off the field Brett Butler won a battle for his life. Butler overcame life threatening oral cancer and not only successfully returned to the field to finish his career, but also successfully influenced others to quit using tobacco.

Butler was born in 1957 in Los Angeles, California. At 5’9″, 155 pounds, Butler was under-sized to play sports. On his high school team, he was not even a full time player on the varsity baseball team, but that did not deter Butler. Though he was small and not the most talented, Butler worked very hard at baseball and eventually became a two time All-American at Arizona State University. But his hard work was not enough to impress scouts, and in the 1979 Major League Baseball draft Butler fell all the way to the twenty-ninth round, where he was drafted by the Atlanta Braves. Though disappointed, Butler set out to prove all the scouts wrong.

After a year in the minors, Butler was called up to the big time. In 1981 he made his debut with the Braves, and got a hit at his first at-bat. This was just one of many more to come, but it was also special because it was a sign that he was going to be a force to reckon with. In the following years with teams such as the New York Mets and Los Angeles Dodgers, Butler enjoyed much success and became one of the best lead off hitters in the majors. For his career, Butler is one of only 26 players to have more than 2,000 hits and 500 steals. He was an All Star in 1991 and has led the league in different years in many different categories such as hits, runs, triples, walks, and games. But all his great statistics on the field could not save him from a tragic event off the field.

In 1996, right before spring training, Butler complained to Dodger’s team physicians that he was having trouble with a sore throat and swollen neck. The doctors recommended that Butler have a tonsillectomy, but he did not want to miss spring training and decided he would tough it out. Throughout spring training Butler was given antibiotics, steroids, and medications to help fight the pain, but he never felt better.

The pain was tough, and Butler questioned whether he could endure it. When he first heard he had cancer, his first thoughts were about his funeral, not his life after the disease. His pain was immense, so bad that he had to swab his mouth with xylocaine, an anesthetic used by dentists to numb pain, before he could eat a meal. Swallowing became a challenge, and anything involving his mouth was painful. But Brett had a strong support system, and with their help he endured the pain. His wife would not let him talk about dying, and his daughter wanted to take away his pain. She told him, “Daddy, I prayed for God to give me your cancer. I know I can handle the pain but I don’t like to see you in it.” The only words Butler can say when he thinks of this support is, “Now that’s what true love is all about.”

The doctors decided they should remove his tonsils. When doctors went to perform the surgery, they were surprised to find a plum-sized tumor in the right tonsil. The tumor was removed and identified as a Squamous Cell Carcinoma and was found to be malignant. Doctors also found that the lymph nodes around Butler’s neck were also involved. The cancer had spread from his tonsil to these nodes. The doctors removed the lymph nodes and after surgery Butler underwent radiation treatment. The treatment was successful, but for the rest of his life Butler must sip on water because the radiation treatments destroyed the saliva glands in his mouth, his constant reminder of the battle he fought.

In less than four months, a determined Butler was back on the field. In his first game back with the Dodgers, Butler came to the plate and was given a standing ovation by the 50,000 fans that had come to the game. An individual with strong religious beliefs, Butler credits his miraculous recovery to his faith in God. He says, “God doesn’t give us more than we can handle if we just have enough faith to trust him.” And while Butler’s rapid recovery is miraculous in itself, just as important is the influence his cancer has had on other tobacco users. He has become an advocate against spit tobacco.

Butler grew up in a home where both of his parents smoked heavily. Butler quit dipping after he had met with a young fan. At a youth baseball camp, butler saw a 10 year-old boy stuffing some dip in his mouth. When Butler asked the boy why he was dipping, the boy told him because “you do it and you’re my hero.” In that instant, Butler made a deal with the boy; if the boy stopped, Butler would quit as well. And to prove he quit, he told the boy,

You’ll know I quit because when I come to bat, I’ll be blowing bubbles.

And Butler never dipped again.

After finding out about Butler’s mouth cancer, many major league players opened their eyes and realized they were headed down the same path if they continued to chew and dip tobacco. Cincinnati Reds reliever Jeff Brantley, when he heard of Butler’s condition, quit chewing cold turkey. He remembers, “I came to the ball park, took the chewing tobacco out of my locker, and put it in the trash can. I’m not going to touch the stuff. I’ve been chewing it for a long time and enjoy it, but life to me is a lot more important than sticking tobacco in your mouth.” Chipper Jones, the Atlanta Braves third baseman, has also made efforts to give up chewing since he heard about Butler. These are just two of many players that have since changed, opening their eyes to the dangers of using tobacco.

Retiring at the end of the 1997 season, Brett’s career stats included 2,375 hits, 558 stolen bases and a .290 lifetime batting average. Now that he has retired, Butler does many speaking engagements, talking about his fight against cancer. He tries to motivate people to work towards excellence in their lives, and continues to educate them on the harms of tobacco and avoiding tobacco use. He exemplifies a life of striving to win, in whatever endeavor he takes on, professional athlete, cancer fighter, and now advocate. Brett’s baseball career and battle with oral cancer show the great potential we all have for overcoming hurdles in life.

Bill Tuttle

The next time you hear the term “smokeless tobacco”, remember the name Bill Tuttle. Joe Garagiola can tell you all about him. Like many professional baseball players, both Tuttle and Garagiola were frequent users of chewing tobacco in the early 1950’s. Garagiola quit. Tuttle kept chewing.

The next time you hear the term “smokeless tobacco”, remember the name Bill Tuttle. Joe Garagiola can tell you all about him. Like many professional baseball players, both Tuttle and Garagiola were frequent users of chewing tobacco in the early 1950’s. Garagiola quit. Tuttle kept chewing.

Garagiola, a former major-league catcher and chairman of Oral Health America’s National Spit Tobacco Education Program often recounts the story of how oral cancer slowly and painfully destroyed his friend.

Tuttle underwent five operations in which parts of his face and skull were removed and rebuilt. Tuttle eventually lost his ability to talk, but not before becoming one of baseball’s most effective anti-smokeless campaigners. He remained passionate about the subject until the very end. A few months before his death in 1998, he scrawled Garagiola a note which read: “Keep up the fight.”

Whether the tobacco is shredded to be chewed or finely ground to be used as snuff placed between the lip and gum, oral use of tobacco – commonly known as “smokeless tobacco” – is not a safe alternative to smoking; some medical professionals consider it to be even more dangerous because of that very belief.

The guy who came up with

[the term ‘smokeless’] should get a huge bonus, because with that one word the tobacco companies really put a whole new spin on this business, be it chew, be it snuff, be it dip,– Joe Garagiola

Garagiola prefers the term “spit tobacco” because it more readily describes the distasteful nature of the product. The implication that spit tobacco is safer because it doesn’t cause lung cancer fails to take into account the fact that oral tobaccos are every bit as addictive and dangerous.

According to the National Spit Tobacco Education Campaign, one “chaw” of chewing tobacco can contain as much nicotine as four cigarettes, which means that the cancer-causing chemicals are that much more potent at the point of absorption, in the gum and jaw area. And what is the user absorbing? Oral tobacco is laced with such toxic chemicals as polonium, a radioactive element which is found in nuclear waste; formaldehyde, the active ingredient in embalming fluid; cadmium, which is also found in car batteries, and cyanide, arsenic, benzene, lead and nicotine, all of which are classified as poisons by the Food and Drug Administration. About 30,000 new cases of oral cancer will be diagnosed in the U.S. this year. Perhaps most disturbing of all, however, is that the median age for spit tobacco users is dropping. Spit tobacco users are on the average starting earlier and earlier in life, exposing themselves to a much higher risk of developing oral cancer.

Since 1970, smokeless tobacco has gone from a product used primarily by older men to one for which young men comprise the largest portion of the market. In 1970, males 65 and older were almost six times as likely as those ages 18-24 to use smokeless regularly. By 1991, however, young males were 50 percent more likely than the oldest ones to be regular smokeless users. In fact, between 1970 and 1991, the regular use of moist snuff by 18-24 year old males increased almost ten-fold — from less than one percent to 6.2 percent. Conversely, use among males 65 and older decreased by almost half — from 4 percent to 2.2 percent.

Additionally, studies show that 4.2 percent of U.S. high school boys (grades 9-12) are current spit tobacco users. Among high school seniors who have ever used spit tobacco, almost three-fourths began by the ninth grade.

My big battle is to convince people that ‘smokeless’ is not ‘harmless.’ ‘Smokeless’ is a nice, fuzzy, protective kind of word, making you think it’s a substitute for cigarettes.

– Joe Garagiola

Why is the spit tobacco market getting younger? Perhaps because they’re being recruited. According to several documents, U.S. Tobacco (UST), the leading manufacturer of smokeless tobacco products, has developed a strategy for new users to graduate them to stronger brands. A document prepared by marketing consultants for UST described the process:

“New users of smokeless tobacco — attracted to the product for a variety of reasons — are most likely to begin with products that are milder tasting, more flavored, and/or easier to control in the mouth. After a period of time, there is a natural progression of product switching to brands that are more full-bodied, less flavored, have more concentrated ‘tobacco taste’ than the entry brand.”

UST controls more than 80 percent of the smokeless tobacco market.

The dangers of spit tobacco are real and verifiable. The nicotine in spit tobacco can cause measurable increases in the heart rate and blood pressure of healthy young men within 5 minutes of use, which can lead to a greater risk of heart attacks and stroke. Spit tobacco causes gingivitis, which may lead to early tooth loss. Spit tobacco can cause oral leukoplakia – a pre-cancerous condition consisting of white, wrinkled, and hardened patches of gum tissue where tobacco is held. The longer spit tobacco is used the greater the risk of both cancerous and non-cancerous oral effects. The risk of developing oral cancer for spit tobacco users ranges from 2 to 11 times that of nonusers. Only half of all oral cancer patients are alive 5 years after diagnosis. Many users of spit tobacco may not notice any immediate health problem as in its early stages, oral cancer symptoms are not outwardly noticeable.

Bill Tuttle never thought he had a problem until the fall of 1993, when he developed a sore in his mouth. His doctor took a biopsy and it came back positive for cancer. The surgeon told him the operation to remove the cancer would take two hours; it seemed a little long, but worth it to remove a cancerous lesion by cutting out “a little piece” of his mouth. ‘”That little piece turned into the biggest tumor the doctor said he ever took out of someone’s mouth,” Tuttle once recounted.

The reconstructive surgery, on Nov. 11, 1993, lasted 13 hours. Skin from his neck was used to replace his cheek, which was riddled with cancer. Then, two slabs of skin were transplanted from his chest up to his neck. During the work on his neck, arm nerves had to be severed, and up until his death five years later Tuttle lost effective use of his right arm.

Then, six weeks later, the cancer returned.

At one point, surgeons rotated part of Tuttle’s skull 180 degrees in an attempt to create a replacement cheekbone. They transplanted muscles from his leg to supplement the tissue cancer had destroyed. For months, he couldn’t swallow. A tube-like siphon had to be inserted into his nose. All this suffering because of that wad of tobacco in his cheek – just because it was associated with the game he loved. That may be changing.

Several organizations have recognized the connection between professional sports and marketing spit tobacco to the youth market.

In 1990, the NCAA banned the use of tobacco in all tournament play. In 1992, Major League Baseball banned spit tobacco for all minor league players in its Rookie and Class A leagues. The idea seems to be that if players are banned from using spit tobacco earlier in their careers, there will be no habit to break later. Even so, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Oakland A’s were among the first major-league teams to address the problem of spit tobacco. Los Angeles banned players from carrying snuff or chewing tobacco while in uniform, and Oakland banned tobacco advertising in its program.

Garagiola claims bans don’t work, but he believes education does. “The NCAA says, If you spit, you sit,'” he has said. “I’ve talked to baseball teams on the college level and every time I find four or five guys who want to quit.” Mike Piazza, Tino Martinez, Alex Rodriquez, Paul Molitor, and Sammy Sosa are among the major leaguers who have taken a public stand against spit tobacco.

If you’re a parent or a coach concerned about a young person’s potential addiction to spit tobacco, there are some things you can do:

Talk. Children whose parents don’t talk to them regularly are at greater risk for experimenting with tobacco. Make a point of discussing your children’s lives and feelings. Make sure you know their friends (and the friends’ parents). That will help you find out whether any of the friends are trying out tobacco, so you can talk about it with your own child.Make your feelings clear. Children who understand the depth of their parents’ opposition to it are less likely to use spit tobacco.

Help children decode ads. Ideally, you should begin as early as the fourth or fifth grade, when children may first become susceptible to the images in spit tobacco or cigarette ads.

Give them a reality check. Point out that, despite the ads, the vast majority of adults do not dip, chew, or spit, and most have never tolerated the practice in public.

Emphasize health. Kids are notoriously unconcerned about getting sick. Tell them anyway: Spit tobacco users are at greater risk for heart palpitations, oral cancer, tooth decay, and a host of other problems. The more years a person uses spit tobacco, the greater the risk of oral cancer in middle age or even earlier.

Emphasize addiction. Nicotine is so addictive that some experts compare it to heroin. And, once hooked, kids find it just as hard to kick the habit as adults do. Trouble is, there’s no way to predict which kids will become addicted. So it’s best not even to experiment.

Don’t use spit tobacco yourself. If you are unable or unwilling to quit, at least explain to your children that you are in the grip of a fearsome addiction, and hide the stuff. Use it less or not at all in front of your children. This self-imposed taboo might even make it easier for you to quit.

Impose consequences. If, in spite of your efforts, you find your child experimenting with tobacco, do not treat it as a minor “kids-will-be-kids” infraction. Treat it as what it is: an act that puts your child at very high risk of developing a life-threatening addiction. Impose whatever sanctions your family uses for a major misdeed. And don’t back down. And, of course, if none of these work, you can always tell them about Bill Tuttle.

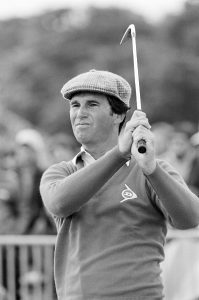

Hubert Green

GULLANE, SCOTLAND – JULY 19: Hubert Green of the USA during the third round of the109th Open Championship played at Muirfiled Golf Club on July 19, 1980 in Gullane, England. (Photo by Peter Dazeley/Getty Images)

The man who Golf Digest called “one of the great players of his generation,” Hubert Green, has become known as much for his successful battle with oral cancer as for his powerful line drives and colorful personality. Though never one of golf’s top stars, between his first big win in 1977 and 1990 Green recorded an impressive 27 top-20 finishes in national tournaments, a strong record that continued after he joined the PGA Senior Tour in 1997. Though his outsize personality earned him both fans and detractors, Green’s public discussion of his experience fighting cancer has drawn support and respect from golfers worldwide.

Hubert Green was born in Birmingham, Alabama on December 28, 1946. He attended Florida State University, where he became a devoted FSU Seminoles fan. After rising quickly through the pro golfing ranks in his twenties, he won the 1977 U.S. Open at age 31, beating previous champion Lou Graham by one stroke. The next year, at the 1978 Masters, he placed second, losing this time by only one stroke, to Gary Player. Green’s golf career was both inspiring and frustrating, as so often he came close to winning only to be beat out by the biggest names of the era-and yet he kept on placing, occasionally showing the golf world exactly what he could do with a club and a lot of tenacity.

As Trevino said of Green in a 1998 interview, “He’s got a wedge and he’s got a putter, but the biggest thing he’s got is guts.” That quality would prove crucial when, at a routine dental cleaning in April 2003, Green was diagnosed with Stage 4 cancer on his tongue and tonsil.

Green reacted to the news with characteristic intensity and humor. On his Web site, hubertgreen.com, he set up a diary in which he tracked his progress for friends and fans, writing in a voice that combined Southernisms, irony, and a strong belief in God, whom he called “Mr. Big.” In his first posting in June 2003, Green wrote:

I want to lay down some basic rules to reading my input. First, I speak in a Southern type of language… Sometimes I might put a capital S after a phrase to emphasize sarcasm. R will stand for red-neckease [S]. I will try to include some highly intelligent digs at y’all from time to time. I will not BS on just how I feel.

Over the next six months, Green detailed the course of his treatment, including digs at the Gainesville chemo nurses (University of Florida fans he teased by bringing in a stuffed FSU mascot, a horse that played the college’s fight song) and gratitude toward his wife Michelle, who he jokingly referred to as “Nurse Ratched”-“She will need to have this transformation since those who know me know just how lovable I can be, especially when… going through a tough time.”

Visitors to the site-and there were thousands-sent in prayers and good wishes, which Green acknowledged in his frequent postings. He also described his cancer treatment in detail, his humor balancing out the medical specifics that did a lot to raise golf fans’ awareness of oral cancer and its treatment options.After his dentist’s initial diagnosis, Green’s story started slowly. Despite a second opinion from an ENT specialist who “didn’t see anything,” Green’s dentist, Stephen Myers, was sure enough of the signs of cancer that he recommended Green to the radiation oncology department at Shands Hospital in Gainesville, Florida, one of the best in the country.

The formal diagnosis came in late May, and his treatment began on July 2: Green would participate in a seven-week clinical trial of IMRT, a new class of radiation that targets the specific area of the cancer, thus saving surrounding areas (in this case Green’s salivary glands on the other side of his mouth).

In between, in June, Green played in three tournaments, including the Senior Open. “What else am I going to do,” he recalled in a 2004 Golf Digest interview, “feel sorry for myself? ‘Oh, woe is me’? I’d have gone crazy sitting at home.” He’d created a successful career playing on the Senior Tour, and had designed several golf courses, including one at Greystone near Birmingham, Alabama, where he’d grown up and where, in 1988, he’d won the Senior Open for the first time. Hubert Green had a life and a career to go back to, not to mention a long and happy marriage, and he was going to have them again if he possibly could.

After seven weeks of radiation and chemotherapy, which he described as a “nine-hole match with the devil,” Green posted a message on his Web site entitled, “MATCH OVER-VICTORY GREEN TEAM.” The match included numerous radiation sessions, in which he wore a mask molded to his face, designed to hold his head still during the procedure. Chemo was referred to, in Green-speak, as “Pukeville.” Green also faced emotional challenges during his treatment. He remembered his father’s death from stomach cancer 26 years before and, in August, dealt with a setback that put him back in the hospital to treat the side effects of the treatment, including pain, dehydration, and a weak immune system. He had continuing trouble eating and swallowing.

True victory was a bit slower to arrive and, as with any cancer in remission, provisional. But as Green reported on his site, checkups through the end of 2003 found him gaining strength and focus, with no sign of the cancer’s recurrence. His weight crept up to 165 from a low of 143 (he previously weighed in at 180), though ongoing symptoms such as earache and a burning sensation on his tongue (what he called “normal bodily reactions to the type of radiation I enjoyed”) continued.

By early 2004, Green was back on the course. A Golf Digest article showed him hitting line drives at his home course, Hombre Golf Club in Panama City Beach, Florida. He was making 145 yards-not even enough for the LPGA, he joked-but his strength was returning. In his last Web posting, on the first day of 2004, Green once again thanked his wife Michelle-no longer Nurse Ratched-his fans and supporters, and “Mr. Big” for “the heavy lifting.” As of this writing, he remains cancer-free and continues to speak of his fight against oral cancer.

Jim Thorpe

A champion famed for his versatility, excellence and drive, Jim Thorpe is known to some as the greatest athlete of the 20th century. Thorpe, who later in life was an oral cancer survivor, is the only American athlete to excel at the amateur and professional levels in three major sports–track and field, football and baseball.

Jacobus Franciscus Thorpe was born in 1888 to Hiram and Charlotte Thorpe of the Thunder Clan of the Sac and Fox tribe, nearly two decades before the territory in which they lived became the state of Oklahoma.. His Sac and Fox name, Wa-Tho-Huk, or “Bright Path” perfectly foretold the course of his life, though profound hardship also shadowed his way.

Thorpe’s childhood path was rocky. He was one of 11 children–six of whom died as children. Like most American Indian children of his day, Thorpe was sent to be taught at Indian boarding schools, starting at the Sauk and Fox Mission School. When his beloved twin, Charlie, died at age 9, Thorpe reacted deeply to the loss, often running away. To keep the boy in school, Thorpe’s parents sent him to the Haskell Institute in Kansas. Two years later, however, Thorpe’s mother died in childbirth. The devastated young teen ran away again, settling for a time to work on a horse ranch. He later reconciled with his father (who died later in Thorpe’s teen years) and began attending the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, and it was there–almost on a whim, legend has it–that Thorpe discovered his abiding love and astounding ability for sports.

One day in 1907, according to some accounts, Thorpe happened to be walking past the Carlisle track during team practice. He spied the high jumpers at drill, decided to give it a whirl, and reportedly still in street clothes, beat them all with a jump of 5’9″. He became a track-and-field record setter for the first time that year. And track was just a warm-up for the sports phenom. He went out for baseball, football and lacrosse, and even excelled at ballroom dancing.

But it was football that brought international fame to the 6’1″, 190-pound Thorpe. His place-kicking and running skills earned him a berth on the 1911 and 1912 all-American teams. He went on in 1912 to the Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, where he was on the U.S. team for four events, even though he would not become an official United States citizen for five more years.

At the Olympics in Stockholm, Thorpe set his most enduring record: he is the only person ever to win gold medals in both the pentathlon and decathlon. King Gustav V of Sweden gave the medals to Thorpe in the closing ceremonies, along with two challenge prizes, saying “You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world.” Thorpe’s reported answer? “Thanks, King.”

Thorpe came home with $50,000 in trophies, then jumped right back into collegiate football, leading the Carlisle Indian School team to the national collegiate championship. But misfortune came back to haunt the young athlete. Soon after his return from Stockholm, a reporter in Worcester, Mass., accurately found that Thorpe been paid for playing baseball in Rocky Mount, N.C., two years earlier. Unlike other amateur athletes who commonly dipped into semi-pro in the summers, Thorpe had used his own name, thinking the pay was so minimal it wouldn’t matter. But when the story broke, Olympic officials investigated. When it was found to be true, Thorpe was stripped of his medals and his achievements were expunged from Olympic records. Thorpe brooded over this loss for the rest of his life. But in 1912, his repositioning as a professional athlete brought major league baseball teams flocking to sign him.

In 1913 Thorpe signed to play outfielder with the New York Giants. He later played with the Cincinnati Reds and Boston Braves, batting .327 in 60 games for the Braves in his last season. Also in 1913, Thorpe married Iva Miller. The two had three children, one of whom, Jim Jr., died at age 2 . In 1915, Thorpe started playing professional football for the Canton Bulldogs in Ohio, earning a then-whopping $250 per game. Thorpe spent spring playing baseball and autumn playing football. In 1920, Thorpe became the first president of the American Professional Football Association, now the National Football League. Thorpe left pro sports in 1929, at the age of 41.

After the end of his athletic career, Thorpe struggled to support Iva and their daughters, Gale, Charlotte and Grace. But sports had been his life, and he was ill-equipped to find and hold work outside that life. His at-times heavy drinking and the onset of the Great Depression didn’t help matters. Thorpe drifted from job to job, at times working as an extra in Western movies, as a bouncer, construction worker, ditch digger. The lifestyle took a toll on his marriage; in 1924, he and Iva divorced. His second wife, Freeda, whom he married two years later, bore sons Carl, William, Richard and John, but that marriage didn’t survive Thorpe’s steadily increasing alcohol addiction and the two divorced in 1941.

Thorpe kept drifting, working odd jobs. Desperate for money, he sold his life story to Warner Bros. for less than $3,000. The film company released Jim Thorpe, All-American, starring Burt Lancaster, in 1951, the same year Thorpe showed up at a hospital nearly penniless and suffering from lip cancer. The hospital accepted him as a charity patient. When word circulated that the once-great athlete was hospitalized and destitute, people from around the nation responded with thousands of dollars in donations.

Thorpe was treated and afterward took work as a greeter in a Los Angeles bar. Two years later, Jim Thorpe suffered a heart attack in Lomita, California, while eating dinner with his third wife, Patricia. He was briefly resuscitated but died March 28, 1953.

In 1982, 29 years after Thorpe’s death, the International Olympic Committee restored his accomplishments to the Olympic record books and in 1983 it presented facsimile medals to his children (the originals were stolen and remain missing). The medals are displayed under a portrait of Thorpe that hangs in the rotunda of the state capitol in Oklahoma City. A senate resolution put forth in 1999 recognizes Jim Thorpe as Athlete of the Century, and a U.S. postage stamp bears his likeness.

“He was the best natural athlete ever,” the New York Times once wrote of Thorpe.” No matter what sport he turned to, he was a magnificent performer. He had all the strength, speed and coordination of the finest players plus incredible stamina. His memory should be kept for what it deserves–that of the greatest all around athlete of our time.”

Charles Robert (“Bobby”) Hamilton, Sr

Charles Robert (“Bobby”) Hamilton, Sr. (1957 –2007) was a NASCAR driver and owner whose down-home, if sometimes gruff, demeanor and blue-collar roots endeared him to fans. Equally at home in a car or under its hood, he continued racing until the progression of his oral cancer made it impossible.

Born in Nashville, Hamilton was a high-school dropout who spent his early days on the short-track circuit in Nashville. Short-track racing, which requires drivers to race at lower speeds on a shorter racetrack, often results in cars “paint swapping” or rubbing up against one another, much to the delight of fans.

It was at the Music City Motorplex, formerly known as Nashville Speedway USA, that Hamilton first gained notice during the weekly circuit races. After winning the track championship in 1987, he raced in a four-car “Superstar Showdown” against three better-known Winston Cup winners. Just a few years later, in 1991, Hamilton himself would be named Winston Cup Rookie of the Year.

His first break came when he was asked to drive one of the movie cars for the 1990 film Days of Thunder, starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman. Although the car was not designed to be competitive, Hamilton qualified fifth in the 1989 AutoWorks 500 in Phoenix. (In the film, the car is driven by character Rowdy Burns.)

Over the next sixteen years, Hamilton competed in more than 370 races, winning two Winston Cups (now known as the Sprint Cup), and was ultimately named 2004 Truck Series Champion. All told, Hamilton’s career included 10 wins, 33 top-fives and 54 top-tens in only 99 starts.

A golden opportunity came his way in 1995 when Petty Enterprises hired Hamilton to drive No. 43. His top-10 finishes that year helped breathe life into the ailing team and helped burnish his reputation as a competitive driver and a smart businessman. He would eventually start his own team, Bobby Hamilton Racing, in 1998.

Among his many wins, Hamilton’s performance at the Talladega 500 in April 2001 was particularly memorable. The first super-speedway race since the death of Dale Earnhardt at the Daytona 500 two months earlier, Hamilton and his fellow drivers faced intense scrutiny from NASCAR and the media in a race that went green the entire way. After exiting his car, an exhausted Hamilton slumped to the ground, requiring oxygen from a tank before he could grant the usual post-win interviews.

In 2006, Hamilton shocked fans and colleagues when he announced that he had been diagnosed with oral cancer. A lump had been discovered after swelling from a dental procedure refused to go away.

“It’s called head-and-neck cancer. I don’t have anything wrong with my head, but [fellow driver Ken] Schrader said a lot of people would doubt that,” Hamilton said, showing fans that his sense of humor was still intact.

The evening after his announcement, Hamilton raced in the Craftsman Truck Series. On the following Monday, he reported for treatment at Nashville’s Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Although he initially hoped to continue racing throughout his treatment, Hamilton abandoned those plans after his second week of radiation and chemotherapy.

“I don’t mind telling you — there aren’t many nights that I’m not scared,” he said. “It’s not scared like being in a haunted house or something. Just little things become important.

“Suddenly things flash in front of your eyes, and seeing your granddaughter raised up means more. Making sure you tell your son you love him means more. Making sure you let the people know around you that you care, and letting your guard down to let other people tell you that they care.”

After competing in three races, Hamilton turned the reins over to his son, Bobby Hamilton Jr., for the duration of 2006. In interviews, he acknowledged how touched he was by the outpouring of support from his fans and colleagues.

In one noteworthy homage, fellow driver Kyle Busch began driving a car with a paint scheme mimicking Hamilton’s car from The Days of Thunder and nicknamed the car “Rowdy Busch.” To this day, Busch has kept the paint scheme and uniform design for many of his short-track races, in memory of Hamilton.

“I want to use what little bit of celebrity status I have left and try to promote the awareness of this disease,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton passed away at the age of 49 on January 7, 2007, surrounded by family in his Mt. Juliet, Tennessee home.

Since his death, his team, Bobby Hamilton Racing, has partnered with cancer organizations to conduct oral cancer screenings for fans and teams alike at NASCAR events. Though not chosen as one of their partners, The Oral Cancer Foundation applauds their efforts to expand knowledge of this disease. The team has also supported St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital.

Ironically, during much of Hamilton’s racing career, the top prize at NASCAR was Winston Cup, sponsored by R.J. Reynolds and Company. As criticism of the tobacco giant’s sponsorship mounted and laws on tobacco advertising became more stringent, sponsorship of the cup eventually went to telecommunications provider Nextel. One wonders how much damage this marketing partnership may have caused to racing fans, and how much might be undone by the Hamilton team’s efforts to raise public awareness about this disease.

Donnie Walsh

In the words of James Dolan, owner of the New York Knicks basketball franchise, “Donnie Walsh is one of the most respected and admired executives in the NBA.” And that is why Mr. Dolan made it his number one priority to convince Mr. Walsh to become the President, Basketball Operations for the Knicks, a team that has disappointed its fans for the past several years and earned a reputation of being one of the most poorly-managed teams in the NBA. Fortunately for Knicks fans, Donnie Walsh has never been one to back down from a challenge. And so on April 2, 2008, he agreed to resign as President of the Indiana Pacers and return to his hometown of New York City.

Mr. Walsh wasted no time taking charge of his new team and planning the strategies that he hopes will enable him to enjoy the kind of success with the Knicks that he enjoyed with the Pacers, who under his stewardship made the NBA Eastern Conference finals six times and the NBA finals for the first and only time in their history. But then, barely two months into his new job, Mr. Walsh underwent a routine exam that revealed a lesion on his tongue that turned out to be cancerous. While his doctors planned his treatment, Mr. Walsh kept his condition to himself and focused on his new team. Roughly one week after the cancer discovery, Mr. Walsh scored a major coup by hiring as his new head coach Mike D’Antoni, who at the time was the highly successful coach of the Phoenix Suns. Less than two weeks after that, Mr. Walsh directed the Knicks efforts in the 2008 NBA player draft. And four days after that, he underwent surgery at New York’s Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center to have his lesion removed.

He waited until the last possible moment to tell his wife about his cancer. “Judy and I have been married 45 years and sweethearts for 50. I know how stressed out I was. I just didn’t want to worry her,” he explained. The weekend prior to the surgery, Mr. Walsh also smoked his last cigarette. He says what had been an uncontrollable 50-year urge to smoke vanished along with the cancerous part of his tongue. Fortunately, the surgery went well. “My doctor says he got it all,” Walsh said. “Luckily, it was caught quickly before it could spread.” Numerous pre- and post-op scans of his head and neck concurred it had been contained.

It comes as no surprise to anyone who knows Donnie Walsh that he would confront oral cancer with everything within his power, as this man has been victorious in virtually every endeavor he has ever tackled. Born in the Bronx in 1941, Mr. Walsh became the all-time leading scorer at Fordham Prep and made first team all-city. He was also one of the school’s top students academically. He attended the University of North Carolina on a basketball scholarship, where he played under legendary coaches Frank McGuire and Dean Smith. He earned both his bachelor’s and law degrees at UNC, where he also met his future wife. He was drafted by the old Philadelphia Warriors of the NBA, but he turned down the opportunity—as well as an offer from one of the most prestigious law firms in New York City—to follow his love of coaching. He took a job as assistant coach at UNC for a brief time before accepting a similar assignment at the University of South Carolina, where he stayed for twelve years. He was then offered the position of assistant coach of the Denver Nuggets by former college teammate and future Pacers coach Larry Brown. Mr. Walsh eventually became the team’s head coach.Mr. Walsh entered the executive ranks when he became general manager of the Indiana Pacers in 1986, and he was named president of Pacers Sports & Entertainment in 1988. In the 1990s, Mr. Walsh also found the time to serve as a member of the U.S. Olympic Games Committee for men’s basketball for Dream Teams I and II. In addition to building a succession of highly successful basketball teams with the Pacers, Mr. Walsh also oversaw the building of one of the country’s premier basketball venues, Conseco Fieldhouse, and the creation of the WNBA’s Indiana Fever. He held this post for 20 years, until he accepted the challenge of returning home to New York to take over the Knicks.

Over the years, Mr. Walsh has also been very active in civic affairs and has served on the boards of numerous charities.

Donnie Walsh clearly loves to compete, and he just as clearly loves to win. While oral cancer is not necessarily the type of competitor he would have chosen to take on, there is no question that, in the case of Donnie Walsh, oral cancer met its match. The foundation wishes him many years of survivorship and good health.