The databases that collect cancer information in the US have been updated. The HARD DATA is in for 2021-2022. Yes, I know that was 4 years ago, but the data always lags reality by about four years. It is a difficult collection of complex data, compiled from different sources, that would be assembled by any other means. The important thing about cancer data is not a single year number, but TREND LINES in the data. The upward trend lines in oral and oropharyngeal cancers remain unchanged from my early years at OCF, and projections indicate this will continue to increase in incidence for most of our lifetimes. I have always believed that some of this is alterable, if not in our generation, in our children’s. But much has to change for that to occur. You should be aware that this is a raw batch of data, and interpreting it and parsing it to get any given number can be done in many different ways. The main database is called the SEER database, kept by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). SEER stands for surveillance, epidemiology, and end results, or essentially what happened, what caused it, and what was the ultimate outcome. More on this further down the post. The other is the National Cancer Registry.

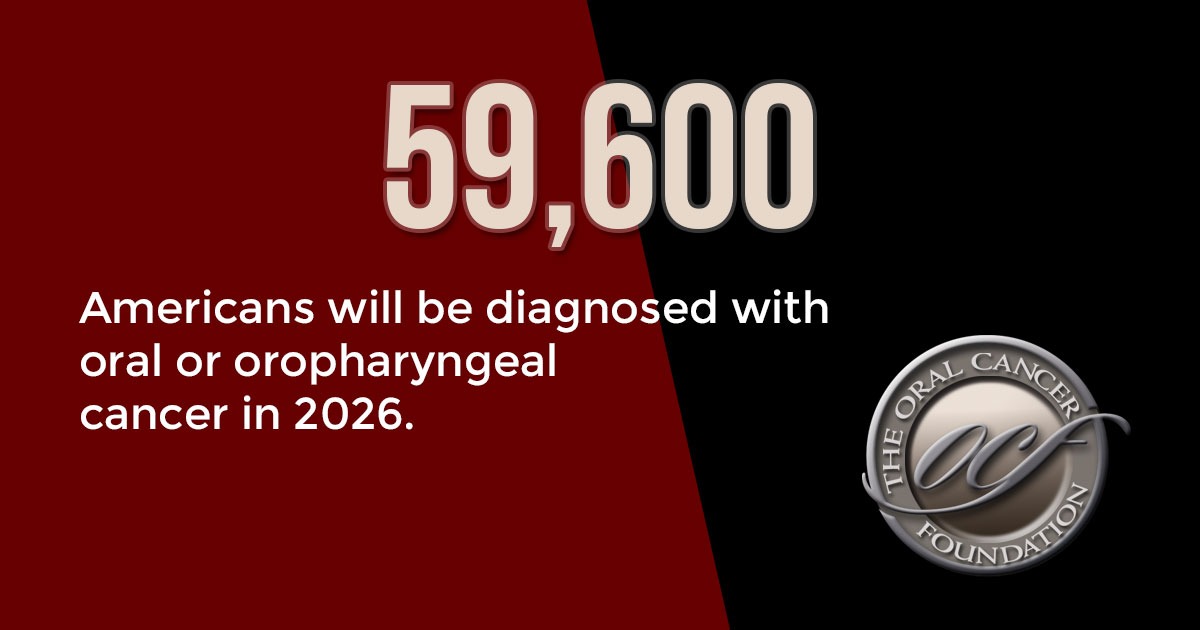

The Oral Cancer Foundation makes an annual prediction of the incidence of oral and oropharyngeal cancers in the US. If you compare our findings to those of others who also calculate this, we are all very similar. I will say this, the way the data are collected does not allow you to know that XX, X26 people are going to have something occur, say an occurrence or a death. The math comes out that way, but the data is not accurate to single digits, probably not to even tens. So we round the final math calculated number. It yields a number you can easily remember, and in the end, it’s not exactly knowable to the single-digit level. This year, the number has increased again, and OCF estimates that 59,600 Americans will be newly diagnosed with oral or oropharyngeal cancer in 2026. Almost 12,750 individuals will die from this cancer in 2026, also an increase over last year. The foundation has been issuing estimates since 2002, and, with a retrospective eye, we have been very accurate. When I started OCF around 1999, the annual incidence rate had held steady for many decades at about 30,000 people. Today we are at 58,500. I find these numbers sobering and sad. Much has changed to cause this, and much needs to be done to reduce these numbers. Many mechanisms to improve this are available to us today, but they are poorly implemented. In this post, I would like you to understand these numbers and how they are collected, so that you have confidence in their validity. In a future post, I will address the reasons we are doing so poorly at bringing this number at least to a plateau, and the obstacles to eventually seeing it reduced.

First, here is an overview of cancer in the US. If you think that we track all cancers in the US, all individuals who get cancer, and ultimately what happens to them, you would be wrong. Understanding the enormity of the idea will make it clear why it is done the way that it is. With a population of about 342 million individuals at the end of 2023, it is estimated that somewhere slightly over 2 million Americans will be newly diagnosed with cancer this year. That is a new record. That number does NOT include most skin cancers (squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas), nor very early findings of carcinoma in situ. About 620,000 deaths will be caused by cancer in America, or about 1,675 people a day. At the end of the year (based on 2022 data), we had access to numbers on survivorship, which can be parsed by cancer type and stage from the dataset, again yielding a best estimate. The number of Americans who have survived a cancer or are currently in treatment is estimated to be about 18.1 million. Cancer is the second most common cause of death in the US, exceeded only by heart disease.

A system that would tell us about every case, covering this large a data set of people, does not exist, and we have no accurate mechanism for collecting such data. What we do is collect data from representative areas of the country and extrapolate (a sophisticated best guess) from that to a national number. The SEER network of institutions that report covers about 28% of the US population. The data collection sites are located in many different geographic locations from rural to urban. But keep in mind that when you see different organizations report slightly different numbers, they are all estimates, as exact numbers are not knowable even in retrospect. These small differences result from some organizations sorting the SEER data differently. When I calculate the OCF’s number, I use ALL incidences of the disease. The database can be parsed in an almost infinite number of ways, by years, by ethnicity, by gender, by age, by stage of disease, and much more. We do not split hairs unless we are looking at a particular age group or subpopulation. The number OCF is issuing today is drawn from “all comers,” with no distinctions based on race, age, gender, etc. Brian