It was twenty years ago this weekend. We measure our lives in milestones of growth and landmarks of experience. Goals aspired to and milestones passed, that show our progress to a destination; be it physical, emotional or spiritual that we have set for ourselves. Others are little more than unset markers of places in the arc of our lives, that we’ve reached at some moment in time. These markers often represent the culminations of efforts, but more often than not, they are just counting off the passage of time. Another notch in the handle of our lives, and for those that contemplate it, another number subtracted from the roughly three billion heartbeats the average human heart will tone in a lifetime. Some are mundane, banal occurrences, others profound and the source of memories that can never be forgotten. My tenth birthday when I got my first REAL bike. My 20th when I spent it in a sweltering monsoon in a foreign conflict, a day that passed without thought of the event, as there was chaos reining around me that usurped any room for other thoughts. Many more of those that just chronicle the passage of time of a life have come and gone. Today is one of those for me.

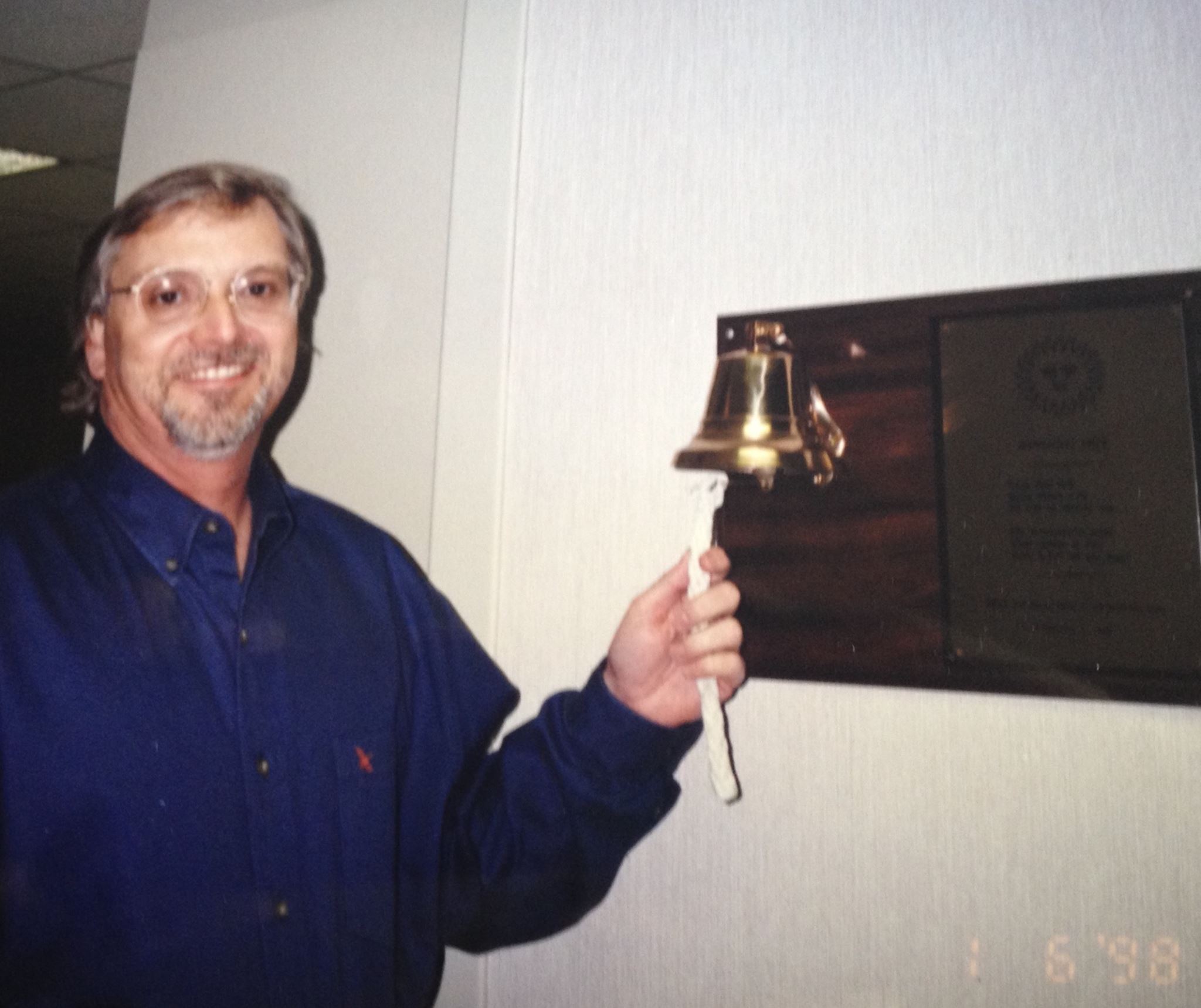

January 6th, 1998 I had my last radiation treatment at MD Anderson Cancer Center and rang the bell on the wall. Here I am at a two-decade milestone, one that I never thought I would reach. For sure it is a cause for some measured celebration. At the time, I never thought I would get to a place very far from the diagnosis, as the treatments were brutal by today’s standards, and my disease very invasive and well developed. When that bell’s tone rang through the waiting area of the radiation department, though this part of treatment was complete, I was not done; and still suspect nodes in my neck were yet to be dealt with by a surgeon’s knife as I had had the maximum allowable dose of radiation for a lifetime. Given the unknown etiology of my disease, and the very advanced state at time of discovery – metastasized into both sides of my neck, things still seemed dire. The doctors lack of experience in dealing with it, and their refraining from speaking much about my future, despite the quality of the institution where I was, was partly due to their lack of long-term survivors to judge from. That left their optimism about my future guarded to say the least. It seemed then, that being here many years out from when a few cells decided to join the dark side, was not something either of us expected nor planed on. I just wish to digress for a moment to explain the distance I, and actually all of us who are survivors of this disese, have come from that point in time.

In 1997, oncology medicine had no clue that the HPV16 virus was causing ANY oropharyngeal cancers, those of the tonsils and base of tongue specifically. Because of that etiology’s cryptic presentation, one without visible lesions which characterized all oral cancers that we knew of at the time, I was part of an observed mystery to my oncology team, a team held in the highest regard at the number one cancer institution in the United States. They had seen a few others like me, but they had no idea why younger men, with no connection to the usual culprit tobacco like myself were showing up on their doorsteps with late stage cancers. Ones for which they could not even find the primary location. We had “unknown primaries,” and very discernable, positive for SCC, neck lymph nodes. The only thing they knew for sure in those days was what is still true today, cancerous positive cervical nodes are never the primary, they are a metastasis from somewhere else. Even in many people’s scans, that “someplace else” was not apparent or discoverable. The only treatment solution to that paradox was a HUGE field of radiation, to hit everything that was even remotely a possible location. For me that extended from my zygomatic arch bones under my eyes to the clavicle bone on my chest. Talk about a large field of radiation…..

Radiation delivery then was far different than it is today. It was not well targeted, and lead blocks that matched the contours of my brain and spinal cord were what kept the deadly beam from destroying those irreparable vital tissues. The understanding of all the important minor places that were likely not cancerous, but still fell within the radiation field existed; but there was no way to map the beam around a cluster of nerves that controlled my systemic blood pressure located in the carotid notch of my neck, nor those that controlled my swallowing reflex in my throat, and many more such anatomical sites. So the uniformity of the radiation beam path passed through and destroyed everything, both good and bad, as they knew the tumor primary had to be somewhere in that field. The idea at the time was the state of the “art.” It was a carpet bombing equivalent idea; an idea where hundreds of bombers deposited their deadly cargo from the skies on a single city at the same time, reducing the entirety of it to ruble in WW2, and created firestorms that raged for days killing the last of the inhabitants be they man, woman, or child that the explosions themselves had missed. Needless to say, the collateral damage to vital structures with this approach was significant. Ironically for me, the very adaptable and flexible IMRT method of radiation was introduced the year after my completion of treatment (1999), though it would take many years to actually be adopted at most major cancer centers, and more importantly for the RO’s at those centers to become conversant in its use. To use it they had to understand and know anatomy as well as a surgeon, something that was not in their training, so the learning curve was significant and transpired over many years. Today, IMRT has for many has reduced morbidities of these treatments when used by someone who creates a map that optimizes impact on the cancerous tissues, while reducing radiation to collateral vital structures.

That same year (1999), I decided that the questions in my mind about the reasons that as a healthy young man, free from tobacco exposure I should come to this cancer, needed an answer. We all think it….why me? The lack of information available to patients was profound even about what we did know. Researching it was within my existing skills, and it seemed a worthwhile endeavor to, while chasing my own answers, help others with access to information about the disease while I recuperated from the cancer experience. In essence, I decided to become a student of it, and through what was a relatively yet to be adopted medium (the Internet) make that learned knowledge available, in plain English, curated and collected in one place, available to others behind me on this journey.

Remember that in 1999, Google existed but was not what we know today, and it couldn’t find its own ass with both hands let alone comprehensive data on oral cancers. Social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, etc. were not to come into existence for many more years. But the potential for reaching a huge audience was there, as was the lack of big costs (outside of an inordinate amount of my time) to make it happen. And OCF was born.

The acquisition of knowledge can be addictive as answers to questions are highly satisfying. I began attending cancer conferences and listening to lectures in earnest, and convinced a group of the smartest people who I could identify to help me in my quest. Initially drawn from the worlds of treatment and research, we started to put vetted information meat on the bones of a web site that was open to the public. Chat rooms were the rage, and while heavily filled with nerds discussing computer issues, sub group sprung up discussing everything from hot rods, to lifestyle topics. But no one was “chatting” about cancer, though university “list-serv” boards existed for those that could find them and navigate a clumsy interface.

I hated the two cancer support groups I attended at different major cancer centers. Overseen by a well-meaning oncology nurse in each case, the 8-15 of us that were in them were all in the same boat. Fresh out of, or still in treatment, we didn’t know anything. Not even the right questions to ask. I was emotionally and physically trashed at the time, and while “misery loves company” is an oft quoted bit of psychology pabulum, it is in reality highly unsatisfying. What a miserable person wants is ANSWERS on how to change things to make them less so. Suffice it to say even given the good intentions of those in the groups, they did not have what I needed. More than that, I was really screwed up still physically, (anyone who has been through this knows that they first 6 months out from treatment are no improvement over what you have been going through) and I need to ask questions and get help EVERYDAY…. Of course these were once a month meetings. What were we supposed to do the other 29 days?

I met a brilliant young code warrior and the Oral Cancer Foundation web site really started to take shape. The most important thing in those early days that he helped me with was identifying, buying and adapting to a completely new need, chat room software to create a cancer support group. There wasn’t anything like it at the time. A few of you here were early adopters of that OCF idea, and we became family. Oral cancer help 24 -7, no matter where you were in the world, for free, and anonymous, and most importantly overseen by oncology professionals that kept the conversations based in fact. Science ruled, and was tempered with plenty of emotional support for those that needed it. As it turns out, opening up about your worst fears and apprehensions in that environment, hidden behind a screen name was way easier than doing it anywhere else. We explored even the taboos like death, which in the first few years haunted the group, and the reality of shared loss of friends from it created a profound bond among those regulars.

Where OCF went over the next two decades touched every aspect of the oral cancer paradigm, and it still breaks new ground today. I would like to tell that story soon, not because of pride, but because it is such an unlikely series of events and characters who have chosen to make it something of measurable value. And I am at a stage of my life where I can see a younger, healthier, equally passionate presence chart the future of the foundation, an idea that at first seemed alien to me, but OCF is not mine. Now with serious accomplishments and longevity, OCF can exist for as long as it is needed. Certainly well beyond me, as this horrible disease is wounded, but not in any immediate sense going to go away and there is still much to do. So here I am looking back today at almost one third of my lifetime. A couple decades that I never thought I would have. I am in so many ways a changed person. I have become more knowledgeable about oral cancer than I ever thought possible, but more importantly I have been given the privilege, and through the OCF vehicle, to use that knowledge in a meaningful and productive way to help others behind me. When I say given, I am not turning as phrase, it is a fact. The community of individuals; researchers, patients, care givers, treatment professionals, educators, families of those lost, dental professionals that became engaged in early discovery, Hollywood celebrities, mega bands, and captains of industry, public servants inside national organizations from the CDC to the NCI, and so many more grew up around me, urged me on, facilitated my efforts, paid for the important research, used their influence to further an idea. It is such a charmed existence that I have lived. I’d like to thank all those who have over the years believed in the idea of OCF and supported it, and me. We have accomplished so much together.