Difficulty eating and swallowing food—dysphagia—can have a significant impact on a patient’s life after radiation treatment and surgery. Consuming enough nutrition is critical to a your ability to recover from surgery and tolerate life saving treatments. Recognizing this disorder early allows you and your doctor to implement an effective treatment plan. In the long term, patients may experience some permanent eating and swallowing disability as a result of treatment, but in many cases this can be treated or compensated for.

“Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a swallowing problem that happens before food reaches the esophagus and may result from neuromuscular disease or obstructions. Patients experience difficulty starting a swallow, food goes down the wrong pipe, or there is choking and coughing. This may result in poor nutrition or dehydration, aspiration (accidentally sucking food into the lungs during swallowing, which can lead to pneumonia and chronic lung disease) or embarrassment in social situations that involve eating…”

Signs and symptoms associated with dysphagia may include:

- Having pain while swallowing (odynophagia)

- Being unable to swallow

- Having the sensation of food getting stuck in your throat or chest or behind your breastbone (sternum)

- Drooling

- Being hoarse

- Bringing food back up (regurgitation)

- Having frequent heartburn

- Having food or stomach acid back up into your throat

- Unexpectedly losing weight

- Coughing or gagging when swallowing

- Having to cut food into smaller pieces or avoiding certain foods because of trouble swallowing

The following information is heavily drawn from an original CE course written by Joy E. Gaziano, MA, CCC-SLP. For the original version of the article

Evaluation and Management of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Head and Neck Cancer

Introduction

Dysphagia, derived from the Greek phagein, meaning “to eat,” is a common symptom of head and neck cancer and can be an unfortunate sequelae of its treatment. Dysphagia is any disruption in the swallowing process during bolus transport from the oral cavity to the stomach. In head and neck cancer patients, dysphagia may be caused by surgical ablation of muscular, September/October 2002, Vol. 9, No. 5 Cancer Control 401 bony, cartilaginous, or nervous structures or may be attributable to the effects of antineoplastic agents including radiation and/or chemotherapy. The severity of the swallowing deficit is dependent on the size and location of the lesion, the degree and extent of surgical resection, the nature of reconstruction, or the side effects of medical treatments. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders present unique challenges to the speech pathologist working with the head and neck cancer population. Successful management requires interdisciplinary collaboration, accurate diagnostic workup, effective therapeutic strategies, and consideration for unique patient characteristics.

Normal Swallowing Function

Swallowing is a complex series of sequential neuromuscular events that are integrated into a smooth and continuous process. To appreciate the potentially devastating effects of oral cancer on swallowing, it is helpful to understand normal anatomy and physiology. Generally, the process is divided into three stages: oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal.

The oral phase is completely voluntary and involves the entry of food into the oral cavity and preparation for swallowing; this includes mixing with saliva, mastication, and formation into a cohesive bolus in preparation for the swallow. It requires coordination of the lips, tongue, teeth, mandible, and soft palate. The pharyngeal phase is initiated as the tongue propels the bolus posteriorly and the base of tongue contacts the posterior pharyngeal wall, eliciting a reflexive action that begins a complex series of events. The soft palate elevates to prevent nasal reflux. The pharyngeal constrictor musculature contracts to push the bolus through the pharynx. The epiglottis inverts to cover the larynx and prevent aspiration of contents into the airway. The vocal folds adduct to further prevent aspiration. The hyolaryngeal complex moves anteriorly and superiorly, which, in combination with the pressure generated by a bolus, provides anterior traction and intrabolus pressure to open the cricopharyngeus. The esophageal phase is completely involuntary and consists of peristaltic waves that propel the bolus to the stomach. Total swallow time from oral cavity to stomach is no more than 20 seconds.

Cranial nerve function is often interrupted in surgical resection of head and neck tumors. Swallowing deficits may result when any one or more of five cranial nerves are affected. The trigeminal nerve (CN V) controls general sensation to the face and motor supply to the muscles of mastication. The facial nerve (CN VII) controls taste to the anterior two thirds of the tongue and motor function to the lips. The glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) provides general sensation to the posterior third of the tongue and motor function to the pharyngeal constrictors. The vagus nerve (CN X) provides general sensation to the larynx and motor function to the soft palate, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus. The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) controls motor supply to the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue.

Evaluation of Dysphagia in Head and Neck Cancer

A comprehensive evaluation of dysphagia should include several medical disciplines including the surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, speech pathologist, radiologist, and dietitian. While each has a role to play, it is usually the speech pathologist who conducts a clinical or instrumental assessment of swallowing function and makes recommendations for therapeutic intervention. A thorough examination begins with a clinical swallow assessment that includes a detailed history of subjective complaints and medical status, pertinent clinical observations, and a physical examination. Swallowing trials can be initiated with a range of food textures. An oromotor examination assesses the function of the oral structures for swallowing. Blue dye testing can be utilized with patients who are tracheostomized to accurately determine the relative risk of aspiration. Cervical auscultation uses a stethoscope on the larynx to detect the sounds of swallowing and respiration. The goals of a clinical assessment are screening for the presence of dysphagia, contributing information as to the possible etiology of the impairment, determining the relative risk of aspiration, ascertaining the need for non-oral nutrition, and recommending additional assessment procedures.

Several instrumental assessments of swallowing exist to provide objective information about swallowing function and safety. The most widely used procedure is a video fluoroscopic assessment of swallowing. It is performed in the radiology department by a radiologist and speech pathologist. Benefits include the ability to view the complex interaction of the phases of swallowing, describe the anatomy changes and dynamics of the swallow, identify the etiology of aspiration, and assess the benefit of treatment strategies during the study. The modified barium swallow is thought to be the “gold standard” for assessment of swallowing. However, the fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) is a useful tool in the assessment of swallowing in the head and neck cancer patient. It consists of passing a thin, flexible endoscope into the pharynx and observing the act of swallowing. It provides excellent visualization of post surgical or post radiation anatomical changes. It can also be used as biofeedback to retrain swallowing function. Scintigraphy, manofluorography, and ultrasound, have all been used as methods of assessment. However they are generally used as an adjunct to modified barium swallow or FEES rather than an alternative.

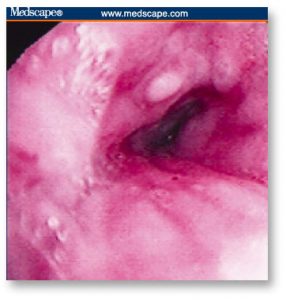

Instrumental assessment of swallowing in the head and neck cancer population provides useful information about both the structure and function of the swallowing mechanism. Patients with oral cavity lesions generally demonstrate swallowing symptoms specific to bolus preparation, containment, and posterior movement to the pharynx. Oral phase deficits that can be identified using the modified barium swallow include insufficient lip seal, impaired mastication, poor bolus control, oral stasis, premature leakage of foods to the pharynx, and structural abnormalities. Tumors located in the oropharynx and/or pharynx may demonstrate a delayed or absent swallow response, reduced pharyngeal contraction, reduced epiglottic inversion, decreased laryngeal elevation, or diminished or uncoordinated cricopharyngeal sphincter relaxation (Fig 1). Laryngeal penetration or tracheal aspiration may occur as a result of the aforementioned deficits.

Figure 1. Post swallow oral (thick arrow) and pharyngeal (thin arrow) stasis in a patient with base of tongue cancer.

Figure 2. Laryngeal penetration (thick arrow) or tracheal aspiration (thin arrow) may occur as a result of post swallow stasis in the valleculae.

Swallowing evaluation using FEES provides information regarding the structure and functions of the pharyngeal phase of swallowing. It offers optimal visualization of the tumor, reconstructed anatomy, and associated treatments, as well as their effects on swallowing. FEES also allows assessment of palatal function in patients with palatal resections and assists the maxillofacial prosthodontist in developing palatal obturators. It also permits inspection of secretion management, a known indicator of swallowing safety.

Effects of Radiation on Swallowing

External-beam radiation has both early and late side effects that can impact swallowing function. Early effects include xerostomia (dry mouth), erythema superficial ulceration, bleeding, pain, and mucositis, which is a painful swelling of the mucous membranes lining the digestive tract . These usually result in oral pain that may cause only minimal diet alterations, require prescription of pain medications, or necessitate reliance on non-oral nutrition. Hypopharyngeal stricture (a narrowing of the pharyngeal structure as a side effect of the radiation) may require dilation or surgery (Fig 3). Xerostomia is a side effect of treatment that persists for years and may worsen over time. Late radiation effects may include osteoradionecrosis (a condition where irradiated bone and surrounding tissues lose their reserve reparative capacity and start to degenerate ), trismus (lockjaw), reduced capillary flow, altered oral flora, dental caries, and altered taste sensation. The late effect of reduced blood supply to the muscle can result in fibrosis, reduced muscle size, and the need for replacement with collagen. This can dramatically affect swallowing years after treatment with a fixation of the hyolaryngeal complex, reduced tongue range of motion, reduced glottic closure, and cricopharyngeal relaxation, resulting in potential for aspiration. Specific swallowing exercises have been shown to reduce these effects and improve prognosis for oral intake. These include jaw range of motion, tongue base range of motion exercises, and effortful swallow exercises, tongue holding maneuver, Mendelsohn maneuver, and super supraglottic swallow. Patients are encouraged to practice these exercises daily during and after treatment since effects of chemoradiation can occur long after treatment completion. As new delivery methods of radiation therapy are developed, such as shielding and intensity modulation, the negative effects of treatment should be reduced.

Figure 3. Hypopharyngeal stricture may require dilation or surgery.

The speech pathologist, as part of the interdisciplinary team, should provide patient education about strategies to reduce the effects of radiation on swallowing. These strategies may include optimal oral hygiene, avoidance of alcohol and tobacco, decreased caffeine consumption, adequate hydration, avoidance of irritating food tastes or textures, and use of artificial saliva or saliva replacement medication. If dental caries are present, dental interventions such as full mouth extractions are considered prior to radiation therapy. Otherwise, daily mouth care, use of topical fluoride, and avoidance of foods that induce dental pain are recommended. In cases of severe osteoradionecrosis, patients are usually converted to a puree diet, liquid nutritional supplements are encouraged, and tube feeding may be required.

Effects of Chemotherapy on Swallowing

Chemotherapeutic agents for head and neck cancer can also cause side effects that impact swallowing and nutrition. They can cause nausea, vomiting, neutropenia, generalized weakness, and fatigue. Anorexia and weight loss are common. Mucositis may cause sufficient pain to require non-oral supplementation. The incidence rate of mucositis has been reported to be approximately 40% for chemotherapy patients; however, it approximates 100% in patients receiving chemoradiation. Symptomatically, mucositis manifests itself in odynophagia (pain) during mastication and swallowing, oral bleeding, dysphagia, dehydration, heartburn, vomiting, nausea, and sensitivity to salty, spicy, and hot/cold foods. Stomatitis refers to chemotherapy-related oral cavity ulcers that result in eating difficulty. The cytotoxic agents most commonly associated with oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal symptoms of dysphagia are the antimetabolites such as methotrexate and fluorouracil. The radiosensitizer chemotherapies, designed to heighten the effects of radiation therapy, also heighten the side effects of the radiation mucositis.

Considerable attention has been given to both prophylactic and treatment measures to counteract the adverse side effects of these medications. Prophylactic measures begin with an increased emphasis on improved oral hygiene. Oral cryotherapy, the therapeutic administration of cold, is a prophylactic measure for oral inflammation. Cryotherapy can be provided in the form of ice chips just prior to chemotherapy and for 30 minutes after drug administration. A marked decrease in the incidence of stomatitis has been noted in patients utilizing cryotherapy. Therapeutic measures to control mucositis and stomatitis include the use of anesthetics, analgesics, anti-inflammatory agents, antimicrobial therapy, and coating agents. Anesthetics are usually used in tandem with mouthwashes or rinses. An oral suspension of diphenhydramine, lidocaine, and an antacid (Maalox) called “magic mouthwash” can be prescribed, which is swished and swallowed for symptom management.

Effects of Surgical Resection

Oral Cavity

Cancers in the oral cavity can cause a range of predictable but complex swallowing problems. The location, size, and extent of the tumor as well as the surgical reconstruction procedure can significantly affect the functional outcome. Groher proposed that the removal of less than 50% of a structure involved with swallowing will not interfere or seriously impact swallowing function. However, Sessions et al showed that the size of the lesion excised was less a prognostic indicator than the area excised and that resultant dysphagia could be predicted in cases of base of tongue and arytenoid cartilage resections. Another complication that may affect swallowing function is the loss of sensation that accompanies the interruption of nerve function with surgery. The use of nonsensate flap closures may interfere with the normal sensation needed to guide the bolus through the oropharynx for efficient swallowing. Additionally, tissue flaps have no motor function resulting in the loss of propulsive force. They also may obstruct bolus passage if they are large and bulky.

Studies show that resections of up to one third of the tongue result in only transitory swallowing problems. Optimal function is achieved when lesions of the anterior tongue are treated with composite resection and when neural control and some tongue movement are preserved. If tongue tethering to the floor of mouth or hypoglossal nerve involvement occurs, the swallowing deficits will be more severe. They may consist of problems with chewing, controlling food in the mouth, and initiating a swallow. Patients undergoing total glossectomy can regain functional swallowing. However, if glossectomy is combined with anterior mandible resection, recovery is poorer because the patient cannot adequately elevate the larynx, which impacts cricopharyngeal opening. Outcome studies show that patients with oral tongue resections that are uncomplicated by involvement of other structures can regain oral nutrition 1 month post-healing. However, a significant percentage of patients must undergo more extensive resections to achieve adequate cancer control.

If the tumor is located in the posterior oral cavity including the base of tongue, soft palate, retromolar trigone or tonsillar fossa, surgical excision usually will cause more severe dysphagia. The tongue base plays a critical role in initiating the swallow, propelling the bolus through the pharynx, and efficient pharyngeal peristalsis. Any procedure that minimizes the tongue base to posterior pharyngeal wall contact can result in reduced pressure generation causing pharyngeal stasis post-swallow, delayed initiation of the swallow resulting in aspiration before the swallow, or reduced hyolaryngeal elevation causing pharyngeal stasis and post-swallow aspiration. Resections of the tongue and hard palate result in loss of pressure needed to propel the bolus into the pharynx. Combined resection of the soft palate and tonsillar pillars may impact bolus transport through the oral cavity and pharynx causing nasopharyngeal reflux and pharyngeal stasis. Patients undergoing glossectomy and submental resections have reduced tongue propulsion and lip sensation. Sacrifice of the hyomandibular constrictors reduces the protective tilting action of the larynx with potential for significant aspiration. Total glossectomy with bilateral neck dissections has a poor swallowing outcome unless the superior laryngeal nerve, hyoid bone, and epiglottis remain intact.

Pharynx

Resection of cancer in the pharynx, including the pharyngeal wall, valleculae, or pyriform sinus, can result in significant dysphagia. The peristaltic contraction begins superiorly and courses inferiorly. Any disruption of the muscular contraction may cause food to coat the pharynx. The larger the pharyngeal resection, the greater the pharyngeal residue. Additionally, surgery that affects the lateral pharynx may cause fixation of the larynx so that it cannot elevate during swallowing. If this occurs, epiglottic inversion is compromised and laryngeal penetration or tracheal aspiration can occur. Scar tissue in the pharynx can also reduce laryngeal elevation.

Larynx

The laryngeal complex serves two critical functions during swallowing. First, the larynx elevates and moves anteriorly under the tongue base to move it from the path of the bolus and to assist in cricopharyngeal sphincter opening. Second, it protects the airway from aspiration by closing at three levels — the epiglottis, false vocal folds, and true vocal folds. Any surgery that compromises this closure, especially of the true vocal folds, will likely result in aspiration during the swallow. Supraglottic laryngectomy can interfere with laryngeal elevation and sometimes vocal fold adduction. If a laryngeal suspension procedure is performed during reconstruction, laryngeal elevation is improved and swallowing is safety enhanced. If a supraglottic laryngectomy procedure encompasses more that the traditional procedure and includes portions of the hyoid bone, base of tongue, aryepiglottic folds, or false vocal folds, prognosis for swallowing recovery is diminished. Patients undergoing vertical hemilaryngectomy generally display reduced laryngeal closure due to the loss of one half of the larynx. If the procedure is limited to a unilateral true and false focal fold, then swallowing recovery is possible with a combination of increased effort during laryngeal adduction and compensatory head posturing. If the hemilaryngectomy extends to the opposite vocal fold, then swallowing recovery is prolonged and may require an exercise program to improve adduction or an augmentation or medialization procedure.

Patients undergoing total laryngectomy have few swallowing problems following surgery due to the permanent separation of the trachea and esophagus. However, occasionally the laryngectomee may have problems propelling the bolus through the oral cavity and pharynx as a result of the loss of hyoid bone, which is the anchor for the tongue. Increased pressure in the pharyngoesophagus following laryngectomy requires the tongue to move with greater force. Stricture at the anastomosis may cause narrowing and reduced bolus flow through the pharynx. Pseudoepiglottis, a postsurgical fold of tissue from the pharynx at the level of the base of tongue, may serve as a mechanical barrier to efficient bolus flow and trap food in its pocket.

Swallowing and Postoperative Radiation

While the extent, type, and location of the surgical resection play a major role in determining swallowing outcomes, the effects of postoperative radiation also may impact swallowing rehabilitation. Irradiated patients have significantly reduced oral and pharyngeal functions including longer oral transit times, increased pharyngeal residue, and reduced cricopharyngeal opening times. Impaired function may be the result of radiation effects such as edema, fibrosis, and reduced salivary flow. Delayed healing and fistula development are more common in radiated tissue.

Goals of Swallowing Rehabilitation

There are several goals in swallowing rehabilitation. The primary goals are to prevent malnutrition and dehydration and reduce the risk of aspiration. Re-establishment of safe and efficient oral intake, prevention of dysphagia prior to medical treatment, and patient education regarding the specifics of their disorder are also important goals of intervention. Pretreatment counseling is beneficial in addressing the possibility that dysphagia may develop during or after the completion of the planned treatment. Poorly prepared patients may become frustrated when attempting to feed and thus may fail to ingest enough to maintain adequate nutrition and hydration. Individuals can be given strategies, recommendations, or exercises prophylactically to reduce the chances of developing a problem. Researchers are currently investigating the benefits of pre radiation exercise. Treatment for post surgical cases usually begins once the surgeon indicates the patient has healed sufficiently, usually 5 to 10 days post surgery. Patients on chemoradiation protocols may receive swallowing therapy during treatment, but often the development of mucositis results in oral pain and prohibits exercise or significant oral intake until after it is resolved. Swallowing therapy can be initiated years after cancer treatment, since the effects of chemoradiation can occur long after treatment is completed.

Treatment Strategies for Dysphagia

For those patients who have undergone surgical resection or organ preservation protocols for head and neck cancer and who are unable to resume functional swallowing, several treatment options are available. Treatment strategies should be introduced during the video fluoroscopic evaluation to determine the effectiveness of the strategy prior to implementation. Several categories of interventions exist including postural changes, sensory procedures, maneuvers, diet changes, physiologic exercise, and orofacial prosthetics. Used alone or in combination, these options can be extremely successful in returning a patient to safe and efficient oral intake.

Postural strategies are simple techniques designed to alter the bolus flow. A chin down posture improves base of tongue contact to the posterior pharyngeal wall, opens the vallecular space, and puts the larynx in a more protected position. Head rotation to the damaged side closes off a weakened pharynx and allows bolus passage down the intact contralateral side. Head tilt to the intact side provides gravity assist in bolus flow through the oral cavity and pharynx. A side lying position may be useful in a delayed swallow or with poor airway protection as it slows the flow of the bolus through the pharynx. Combinations of these strategies can be used with an additive effect.

Sensory procedures provide altered sensory feedback or sensory enhancement during swallowing. Alterations in bolus volume, taste, and temperature can be used to affect changes in swallowing physiology. For example, cold and added pressure (thermal-tactile stimulation) have been shown to increase the speed of initiation of the swallow response. Added pressure on the tongue by a utensil also increases sensory feedback. Since chewing sends sensory information to the pharynx, a soft masticated diet should be utilized when possible. Finally, the sensory motor integration achieved during self-feeding helps to normalize swallow patterns. Therefore, patients should feed themselves whenever possible.

Extensive data exist regarding the efficacy of swallowing maneuvers in the head and neck population. They are designed to alter the physiology of the swallow. The supraglottic swallow maneuver closes the vocal folds before and during the swallow. The effortful swallow improves tongue base retraction and pressure generation. The Mendelsohn maneuver enhances and prolongs laryngeal elevation and anterior movement to improve laryngeal elevation and extent and duration of cricopharyngeal opening. The tongue-holding maneuver improves the tongue base to posterior pharyngeal wall contact and exercises the glossopharyngeal muscle. Dry or repeated swallows reduce pharyngeal residues.

Diet alterations and food presentation strategies also can be use therapeutically to improve efficiency and safety of swallowing. Thickening liquids may slow the rate of bolus flow through the pharynx for patients with a delayed swallow. A puree diet can be used if surgical resection or trismus prevents chewing. Foods prepared with sauces and gravies may be useful for a xerostomic patient. Alternating solids and liquids can reduce pharyngeal stasis. Liquids can be presented by cup, straw, spoon, or syringe, depending on specific patient needs. Chopsticks or an iced teaspoon can place foods in the posterior oral cavity. A glossectomy spoon is specially designed to push food into the pharynx, bypassing the oral phase of swallow. Food placement on the surgically unaffected side can increase efficiency and safety as well. All of these dietary changes can be used in combination with postural alterations and swallow maneuvers at mealtime.

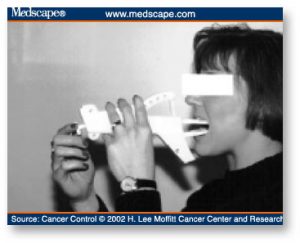

Range of motion exercises for the jaw, lips, oral tongue, tongue base, upper airway closure, and laryngeal elevation are useful for head and neck cancer patients who have structural or tissue damage. Resistance exercises are used for strengthening musculature. Exercises can be enhanced with new technology and devices. The Therabite (Therabite Corp, West Chester, Penn) improves jaw range of motion in patients with trismus (Fig 4). The Swallowing Workstation (Kay Elemetrics Corp, Pine Brook, NJ) provides biofeedback for a range of treatment applications (Fig 5). Surface electromyography (EMG) biofeedback provides visual and auditory feedback for added motivation and success during therapy. Surface EMG combined with respiratory tracing can provide feedback on the coordination between respiration and swallowing. Video endoscopy can be used to view vocal fold closure associated with swallowing. Intraoral tongue array sensors provide visual biofeedback during tongue-strengthening exercises.

Figure 4. The Therabite rehabilitation system improves jaw range of motion in patients with trismus. Copyright Therabite Corp, West Chester, Pa. Reprinted with permission.

Oral prosthetics can offer structural support and compensation to oropharyngeal structures that were lost or altered post surgery. Palatal lowering prostheses recontour or lower the palate to allow the remaining portion of the resected tongue to contact the palate when swallowing. Obturators can fill a palatal defect, preventing food leakage into the nasal cavity and establishing more normal intraoral pressure. Use of these devices can significantly reduce oral residue. The speech pathologist collaborates with the maxillofacial prosthodontist to provide feedback on the configuration, use, and benefits of the prosthesis.

Nutritional Issues

Nutritional changes related to dysphagia are another concern for patients with head and neck cancer. The side effects of treatment can contribute to malnutrition and dehydration in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer patients have the highest incidence of protein calorie malnutrition of all hospitalized patients. Approximately one third of patients with advanced head and neck cancers are severely malnourished and another third of them experience mild malnutrition. The degree of malnutrition is related to the patient’s nutritional status before tumor development, to the characteristics of the tumor, and to the cancer treatment itself. Aggressive cancer treatments may worsen the severity of nutritional status. In severe cases, interruption or discontinuation of cancer treatment may be required.

Head and neck surgery can have a negative effect on nutritional status due to loss of swallowing function and cosmetic deformities. Alterations in taste and smell may affect enjoyment and motivation to eat. The increased time required to consume a meal with a structural alteration may reduce the amount of oral intake. Diet modifications, such as a liquid-only diet, may result in reduced caloric intake. The physical effort of swallowing or the accompanying pain may also render patients unwilling or unable to meet the nutritional requirements for optimal healing.

Radiation therapy can also have a deleterious effect on nutritional status. Used as a primary intervention or as an adjunct or palliation, radiation can cause xerostomia, stomatitis, mucositis, dysgeusia, dysosmia, and odynophagia. Pain from mucosal ulcerations can lead to reduced intake. Many patients develop food aversions or loss of taste sensation due to radiation-induced damage to the taste buds. Xerostomia, caused by damage to the salivary glands, may become progressively worse during and after treatment. It can be a factor in poor nutrition as a result of reduced tolerance to various food textures, temperatures, and acidities. The thick, ropey secretions that may result often interfere with adequate intake.

Chemotherapeutic agents can negatively impact nutritional intake primarily as a result of its effects on the lining of the oral cavity, oropharynx, and esophagus, causing mucositis and odynophagia. Contributing to cachexia and malnutrition are the side effects of nausea and vomiting. Cisplatin, a chemotherapeutic agent frequently used in head and neck cancer management, has a high emetic potential. Diarrhea, constipation, and malabsorption also may occur. These side effects generally subside shortly after treatment has been completed. However, without nutritional intervention, the effects of the undernourishment can be long-lasting. Combined chemoradiation can put patients at even higher nutritional risk due to the combined toxicities of the two modalities and their effects on swallowing.

Although nutritional support does not directly improve survival rates, proper nutrition and hydration can improve tolerance to cancer treatments and functional outcomes. Patients also experience fewer complications and express a greater sense of well-being. Fewer rehospitalizations occur with those patients who receive early nutritional interventions and supplemental nutritional support. Interdisciplinary interventions by the dietician and speech pathologist can help to ensure that adequate nutrition is achieved by either oral or non-oral routes.

Psychosocial Issues

Dysphagia resulting from head and neck cancer has psychosocial implications. Patients are often unprepared for the emotions they encounter when mealtime consumption is significantly altered. The inability to participate in mealtimes and dining out as they are accustomed to can be isolating. Increased mealtimes, limited food choices, special food preparation methods, and untidy consumption contribute to avoidance of social food consumption. Family relationships can be altered when substantial lifestyle modifications are encountered. Patients may become dependent on the medical providers and family members for basic care and emotional support. After cancer recovery, patients may experience distress related to return to work and the alterations in the feeding process. Use of tube feeding, diet modifications, adaptive equipment, or rehabilitative strategies for safe and adequate intake can call attention to themselves and thus become a source of anxiety.

The financial impact of dysphagia is evident in the cost of non-oral tube feeding supplementation. If patients cannot return to oral intake, the financial burden of lifelong tube feeding formula can be significant. Patients are often uninsured or under insured. Special meal preparation, equipment, and meal supplements can also contribute to added financial burden.

Self-esteem can be affected when normal facial appearance or communication ability is altered by surgery. Altered facial appearance also can lead to social isolation and psychological distress. Pain and fear of disease progression or recurrence can result in physical and psychological symptoms that require interventions from psychosocial and pain management team members. Withdrawal from tobacco and alcohol throughout the treatment process also requires special interventions from the appropriate disciplines. Substance withdrawal can result in behaviors such as anxiety, irritability, and decreased cognition that can affect the success of the swallowing interventions provided by the speech pathologist.

Pretreatment counseling by all team members including the speech pathologist should focus on identifying a patient’s unique learning needs, cultural preferences, coping skills, support systems, and financial situation. In addition, information on substance abuse history, cognition, and communication skills will provide an understanding of the patient’s ability to participate in the rehabilitation process. Compliance with treatment recommendations is also enhanced when cultural and religious practices are identified and incorporated into the plan of care. Various religions have specific regulations regarding food and food preparation. Patients of varying cultures have food preferences, cooking styles, and customs unique to that ethnic group. Pretreatment counseling about the anticipated swallowing deficits and functional outcomes should be provided. All team members play a critical role in preparing the patient and family for the head and neck cancer intervention.

Post treatment psychosocial and behavioral interventions by the speech pathologist include treatment of the swallowing disorder and any resulting communication impairment. Education and support about altered body image, lifestyle changes, nutrition, and community resources are provided in close collaboration with the physician, nurse, dietician, social worker, physical therapist, pharmacist, psychiatric professional, and other pertinent team members. Participation in support groups encourages improved coping, socialization, and physical recovery.

Conclusions

Evaluation and management of swallowing disorders in head and neck cancer patients present unique challenges to the rehabilitation team. Evaluation of the patient must take into account not only the structure and function of the swallowing mechanism, but also the side effects that the chosen medical interventions will impose. Assessment of unique patient characteristics, including medical history, nutritional status, cultural preferences, coping style, support systems, and communication and cognitive abilities, is crucial in developing a treatment plan that will enhance functional outcomes. Treatment should be designed to improve the safety of oral intake, normalize nutritional status, reduce the complications of the cancer treatment, and enhance the quality of life. Accurate identification and efficient management of swallowing disorders are best accomplished in an interdisciplinary team environment.

The information provided here was largely derived from original work published as a CME course by Joy E. Gaziano, MA, CCC-SLP, Speech Pathology Department at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, Florida.